Paulo Coelho, in a blog post inviting others to steal his books, recently shared the idea that all writers are only recycling four stories.

First, because all anyone ever does is recycle the same four themes: a love story between two people, a love triangle, the struggle for power, and the story of a journey.

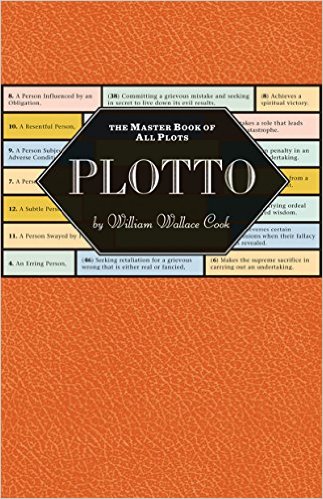

I collect ideas of this kind. Aristotle said there were only two stories, Comedy and Tragedy. We know quite a lot of what he thought about the latter, but his ideas on the former have been lost for some years. Arthur Quiller-Couch devised the rather Man centric seven plots of Man vs. Man, Man vs. Nature, Man against God, Man vs. Society, Man in the Middle, Man & Woman, Man vs. Himself. Also weighing in for the number seven is Christopher Booker, who puts forward a convincing argument that all plots revolve around the conflict between humanity and our selfish ego, only then to ruin it by trying to argue that all 20th Century literature represents the capitulation of the the self to the ego. George Polti outlined Thirty-Six Dramatic Situations including Deliverance, Pursuit, Disaster, Revolt and thirty two more. Perhaps my current favourite has recently been republished in Plotto : the Master Book of All Plots by dime novelist William Wallace Cook which represents a possible 1,462 plots. Wallace once wrote fifty-four novels in one year. Take that NaNoWriMo fanatics! In probably the most famous typology of story, Joseph Campbell trumped everyone by declaring there was only one plot and naming it the Monomyth, thereby determining the formula for almost every Hollywood blockbuster from Star Wars to The Matrix, Toy Story and The Dark Knight.

Are these theories actually of any use? No idea. I like reading them, and from a commercial perspective the Monomyth has proved to be a horrendously successful formula for very, very, very profitable stories. But I completely understand the writers who cover their eyes and ears the moment any mention of this kind of idea appears, for fear that it will forever pollute their original voice.

Are there really only two, seven, thirty six or however many plots? Again, who knows. I’d love to argue for the infinite mutability of story, and I’m sure I could quite convincingly. But at the same time stories, however diverse they appear on the surface, are all made from much the same thing underneath. Some characters. A plot. A theme or two. Half a dozen symbols. A bit of conflict to get it all going. And yet, much like the seven chords that make up all songs, the same elements used in much the same ways seem to yield staggeringly different and original results in the hands of each artist who picks them up. There may only be seven stories, but there are uncounted storytellers, and each one must contribute some unique spark, or the story will never take life.

Very interesting – and to have Quiller-Couch mentioned in any context takes me back! I have always liked E M Forster in ‘Aspects of the Novel’ when he wrote about the difference between story and plot. Once Upon a Time there was a king and queen, and the queen died = story. Once Upon a Time there was a king and queen, and the queen died – of grief = plot.

Nifty.

LikeLike

“In the brief prose ‘The Four Cycles’, he [Borges] reviews four stories: one about a city sieged and defended by brave men (the Troy of the Homeric poems); another, the story of s return (Ulysses comes back to Ithaca);the third, a variation of the last, is about a search (Jason and the Golden Fleece, the thirty birds and the Simurg, Ahab and the whale, the heroes of James and Kafka); and the last one about a sacrifice of a god (Attis, Odin, Christ). Borges then concludes: ‘Four are the stories. During the time left to us we will continue telling them, transformed.'”

(From “Borges and the Kabbalah”, p. 184 – http://books.google.com.br/books?id=-t_-9L5a26QC&printsec=frontcover&hl=pt-BR#v=onepage&q&f=false)

You can read “Los cuatro ciclos” (in Spanish) at http://griegoantiguo.wordpress.com/2009/09/21/borges-y-las-cuatro-historias/

LikeLike

There are exactly 1,604,988,540,133.5 plots, and once they’re used, they’re completely used. The .5, incidentally, is just Nicola Barker’s Darkmans with the sentences “Consubstantiation over transubstantiation? You’d have to be some kind of mad Italian lawyer to believe that” strategically placed at the exact point where it can completely alter the context of the remaining story.

Facetiousness aside, Wondermark provides a genre-fiction generator that seems to be the sure making of a bestseller. Let’s give it a whirl:

http://wondermark.com/554/

“In a post-apocalyptic Soviet Russia, a young author self-insert stumbles across an enchanted sword which spurs him into conflict with a profit-obsessed corporation, with the help of a cherubic girl with pigtails and spunk and her reference book, culminating in convoluted nonsense that squanders the readers’ goodwill.”

The Revenoiacs will be racing up the bestseller charts later this year, once I’ve written it.

LikeLike

I’ve read Campbell and agree he’s served Hollywood rather well over recent years. But stories are slippery things. And, even if there are only a few of the buggers, there’s a million ways of grabbing hold of them and flapping them about. Is there such a thing as a ‘master story’? One story to rule them all, if you like? Like you, Damien, I don’t know.

Unless, of course, we accept that the one true story is simply: ‘This happened, then this happened, then this …’

LikeLike

Maybe an important point to make is that, however many stories there are, turning to a framework like the Monomyth can’t replace having read and analysed thousands of stories. I find ideas like the mono myth useful for deepening my understanding of knowledge I already have. We learn these patterns from the stories themselves.

LikeLike

Absolutely. Actually, I think it works like genetics. The basic proteins – the monomyth if you like – are universal across all species (don’t they say we humans share at least a quarter of our DNA with dandelions?). But who, just by studying those proteins, could imagine life forms as diverse as elderflowers and elephants? The only way to understand stories is to get your hands dirty and read the damn things.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The genetics analogy is excellent. Prompts me to think about memes as the cultural equivalent of genes…

LikeLike

I gave up on Christopher Booker when he tried to argue that mystery/crime novels weren’t proper stories.

I’m not sure why there’s such a reductionist drive for stories. I’ve always thought storytelling akin to composing. Sure, there are a limited number of fundamentals, rather like music has notes and scales, but would anyone ever claim there are only seven basic melodies?

LikeLiked by 1 person

I liked Booker’s�er�book (sounds strange that!) as far as it goes, which is archetypal storytelling. You certainly see those archetypal elements again and again in stories. It really fell down for me when Booker completely misinterpreted almost the entire history of 20th C lit. I don’t remember his bit on mysteries, think maybe I skipped it.

There are only seven major chords in music. And most songs use only three or four in combination. And yet all that variety comes from them. Understanding the archetypes doesn’t necessarily mean repeating them. It can lead more originality, rather than less.

LikeLike

There are bazillions of motifs in music, but probably fewer than 100 conventional ways of developing them at different lengths and complexities (e.g. 12 bar blues, sonata, pop song with bridge, etc.). Plot may be more like those “methods of development.” You think up an interesting situation and people in it, but then there’s only a fairly small number of ways of developing it into a finished narrative.

Or then again, maybe not.

LikeLike

Thanks for commenting John. That makes a great deal of sense to me. I’ve been teaching Samuel Delaney’s idea of dramatic structure recently – Location, Action, Climax. much like songs have verse, chorus, bridge. It’s difficult to get away from those parts.

LikeLike

good post. There are a finite number of stories whatever the exact number is. But as you intimate with your conclusion, story is only one element among several in a writer’s quiver on which to hang a book. It ought never to be the one pushed out front and central.

I think Aristotle also said the essence for a good story was having a beginning, middle and end. I disagree with him there too! I’ve written stories that do not follow such structure.

Story is an armature, not THE book itself.

LikeLike