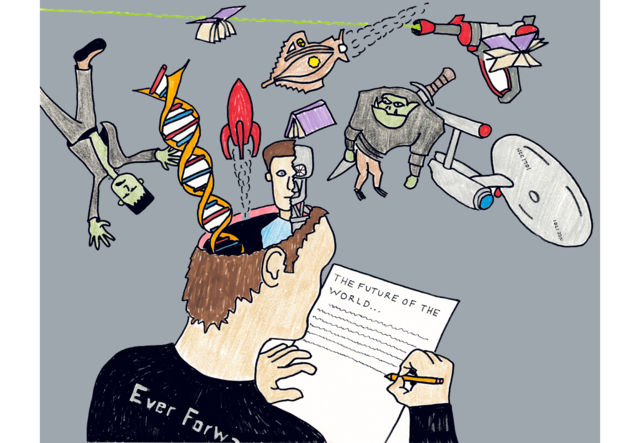

Science shows us how the world is built. Can science fiction help us build a better world?

Follow @damiengwalter on Twitter

The Blue Marble

Astronaut Jack Schmitt released the shutter on the 70 millimeter Hasselblad camera at 5:39 AM on 7th December 1972. The Apollo 17 mission to the moon was 45,000 kilometers from Earth. The image that it captured was not the first of its kind. Other photos of Earth had been recorded by previous space missions, but none so clear and potent as this one.

“The Blue Marble”, as it would later be nicknamed, shows a fully illuminated Earth of white clouds, blue oceans and the continental landmasses of Africa, the Arabian peninsula, and the south polar ice cap. For hundreds of thousands of years, humankind lived on Earth’s surface. Now we could look back and see Earth as a whole, like a child’s marble, shining against the darkness of the cosmos.

In the same decade the Apollo missions were taking a handful of men into space, the rest of humankind were boldly going where no man had gone before. Not on rockets, but in stories. Star Trek was just one in a wave of television shows, movies, comics and books that took readers on journeys of imagination into the unknown reaches of space. Science fiction stories had been around for decades, but the space race between America and the Soviet Union gave them a new energy and importance. When Jules Verne penned From The Earth to the Moon in 1865, its description of a manned mission to an Earth satellite seemed like a flight of fantasy. As the Apollo 11 mission touched down on the lunar surface just over a century later, Verne’s words read like a startlingly accurate vision of the future unfolding before us.

It’s not outrageous to think that science fiction inspires science. Captain James T Kirk’s five year journey on the starship Enterprise inspired both the name of the first space shuttle, and some of the mobile phones we carry today were modeled on Star Trek communicators. In the 1980’s the “cyberpunk” stories of William Gibson were an intrinsic part of the emergence of “cyberspace” and virtual worlds. As Albert Einstein stated, “Imagination is more important than knowledge.” Knowledge is limited to what we know, while imagination reaches into the unknown. As science radically expanded what was known through the 20th century, we needed ever more powerful feats of imagination to guide its development and shape its outcomes. And among the most important products of the 20th century imagination was science fiction.

The scientific revolution that allowed us to send rockets into space was also transforming our understanding of the world we were leaving behind. Centuries of cartographic surveying had outlined and detailed the world’s continents. A revolution in transport meant that the journey around the planet described in Jules Verne’s Around the World in Eighty Days could be completed in eighty hours or less. Just one year before the “Blue Marble” photo was taken, the Intel Corporation produced the first commercial microprocessor chip. The information technology this new computing power allowed would, by the early 1990s, see the advent of the Internet. “The Global Village” – a counter culture concept coined by media theorist Marshall McLuhan – was becoming a reality. Millions of humans flocked to join the emergent Internet, through which they could communicate as easily with peers on the other side of the world as with strangers who lived next door.

The 7.12 billion people living on Earth today are arguably the first cohort of humankind to understand our world from a truly planetary perspective. On the physical plane we have mapped every square meter of the planet’s surface, modelled the tectonic movements of its core and can predict the atmospheric patterns that shape its weather. In the social sphere, we are ever more adept at understanding the tremendously complex, interrelated behaviours of the seven billion people who populate the globe. From economic forecasting to the immense power of “big data”, used to exploit the hidden patterns in human behaviour, we have unprecedented insight into the operations of our society. Cognitively, we can look in to the grey matter of the brain to understand its functions, and employ a century or more of psychological learning to understand our thoughts, feelings, and emotions. And on the grandest scale of the cosmos itself, we can place the blue marble of our world in a dynamic galaxy, itself a mere speck in a universe that grows ever more infinite as we probe its depths.

The “Blue Marble” showed us an Earth both more beautiful and more fragile than we had imagined. The image became symbolic of a burgeoning environmental consciousness. Our planet was no longer a boundless wilderness to be conquered, but a finite resource to be conserved. And science was showing us the many systems that made up the planet and governed life upon it; systems that, once thrown out of balance, might never be brought back under control.

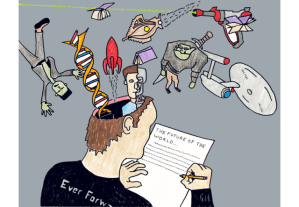

As we look ever deeper int the physical, social, cognitive and cosmic systems of our world, we are lead to ask a simple but profoundly important question: Can we build a better word? Can we apply the systematic understanding of the world science has given us to improve these systems? And like the most complex of mathematical problems, can we find a solution that will bring balance to the world.

In looking for an answer we might find that science is both our greatest tool and our worst enemy. Science has given us such a detailed insight into the systems of our world that not one of us can hope to hold more than an infinitesimal fragment of it in our heads at any one time. Isaac Newton, the natural philosopher who contributed much to the emergence of modern science, was still able to range widely across the emerging fields of physics, chemistry and biology. Today, to understand just a single specialization in the vast sea of human knowledge seems the task of a lifetime.

In looking for an answer we might find that science is both our greatest tool and our worst enemy.

Equally problematic is the conflict between science, religion and the arts. In defining its pre-eminence in the world, science rejected many of the ways of seeing that preceded it. Today any attempt to bring religious or spiritual teachings into the public debate becomes immediately divisive. And science also suffers from its own fundamentalism; a materialist philosophy that rejects all internal experience as invalid, meaning that art of all kinds is also devalued and pushed aside.

Solving a problem as complex as building a better world is going to need unusual tools. We’re going to need a forum where thinkers can merge ideas across the sciences to see what new synchronicities emerge, and a place where our imaginations can explore the incredible possibilities that knowledge opens for us. And because at the heart of our problem are seven billion emotional, erratic and unreasonable human beings, we’re to need tools that look deep inside the human experience. Tools that are every bit as much art as science, and as open to the products of imagination as of reason.

We’re going to need the tools of science fiction.

World Building

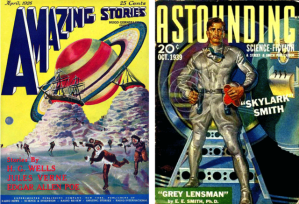

Science fiction was shaped in the pages of pulp magazines in the 1920s and 30s, when stories of alien life, machine intelligence and galactic civilizations became mass entertainment. Critics have dated the emergence of science fiction to the novels of Jules Verne and H. G. Wells in the late 19th century, or the publication of Frankenstein : A Modern Prometheus by Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley in 1818. As a form of modern mythology, science fiction continues in the tradition of fantastic story-telling reaching back to the roots of human civilisation.

In his essay “Fantastika and the World Storm”, author and critic John Clute outlines a history of science fiction that begins in 1750, at the dawn of the Enlightenment and the scientific revolution that would shape the modern era. Science fiction, in Clute’s schema, emerged as a “planetary literature”, one which could consider the ideas emerging from science and envision the vast changes, both good and bad, they would unleash upon the world.

Science fiction is defined by the storyteller’s craft of world building. The world at the heart of a work of science fiction might be our own planet Earth, in some near future or alternative history. Or an alien planet in orbit of a distant star. But the worlds of science fiction aren’t limited to rocky spheres floating in space. The world of a science fiction novel can be a galactic empire, an alternative dimension, an imaginary kingdom, a political state or any of thousands of distinct worlds. Every element of the story – its characters, setting, plot lines and events – are integral to that world and its future. The hero is not just the center of the story. They are the center of the world.

We’re going to need a forum where thinkers can merge ideas across the sciences to see what new synchronicities emerge, and a place where our imaginations can explore the incredible possibilities that knowledge opens for us.

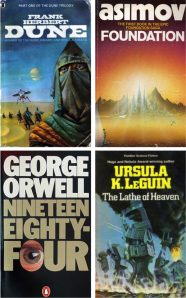

Issac Asimov’s Foundation series charts the fall, and eventual rise, of the Galactic Empire, a human civilisation spanning the Milky Way galaxy – the world the story encompasses. Hari Seldon, the story’s hero, is a mathematician who specializes in “psychohistory”, a scientific discipline that allows him to predict two possible futures: one where a thirty-thousand year dark age overcomes the Galactic Empire, and another where after only one thousand years a new, utopian society arises. By establishing two foundations at opposite ends of the galaxy, Hari Seldon attempts to ensure the second of these futures.

Frank Herbet’s Dune centers on the young Paul Atreides, heir to the doomed House Atreides, who will become the Emperor of the Known Universe. The desert world of Arrakis is the centre of that universe and the source of the spice Melange, the only substance that allows galactic travel. He who controls the spice, controls the universe, and through a process of mystical enlightenment and open warfare, Paul Atreides learns the secret of the spice.

Ursula K. LeGuin’s The Lathe of Heaven depicts a near future Earth, a global society ravaged by poverty and resource wars. At the center of this world is George Orr, a man whose dreams can change the nature of reality, and William Haber, the psychiatrist who tries to shape Orr’s dreams to make a better world. Together they seek to solve racism and overpopulation to bring about world peace, all with unfortunate and counter-productive effects.

A vast array of concepts collide in the stories of Asimov, Hebert and Le Guin. The ability of economics to both predict and shape social change. The politics of empire, colonialism and the long span of history. The emerging ecological awareness and new age spirituality of the counter culture. Resource scarcity, and the fates of worlds in conflict for finite sources of energy. Post-modern philosophy and the conflict between objective reality and subjective experience. It is this melding of disparate ideas into coherent narratives has become the hallmark of science fiction.

These imagined stories – like thousands of other science fiction tales told in the 20th century – were presented to audiences as popular entertainment and escapism. But there was a greater purpose implicit in the emerging literature of science fiction. For most of human history stories had embraced both reason and the imagination. From the earliest recorded story, the epic of Gilgamesh, to the Biblical stories recorded in Genesis and other religious texts. The myths of ancient Greece and Rome, the fairy and folk tales of Medieval Europe and the courtly masques of Shakespearean theatre, for most of human history stories were shaped from both the real and the imagined.

But as we embraced the age of science and reason ushered in by the Enlightenment, a tradition of purely realistic storytelling emerged that set aside the products of imagination. The modern novel, shaped by generations of writers – Honore de Balzac, Leo Tolstoy, George Elliot, Marcel Proust, Jane Austen, Fyodor Dostoyevsky, Charles Dickens, Virgina Woolf, Jack Kerouac and thousands upon thousands more, became the natural home of realism. By the late 19th and early 20th century the realist tradition dominated contemporary culture. Stories that grew from the imagination of the writer, and those resembling the older stories of myth and legend, were thought fit only for children. The imagination was sidelined as a source of mere escapist entertainment and the stories that came from it were seen as pure fantasy.

The Inklings were a group of writers who – between the two world wars in the university town of Oxford, England – were drawn together by the idea of creating stories which recaptured the imagination. Among them were C. S. Lewis, whose “Narnia” novels would enchant a generation of children, and J. R. R. Tolkien, whose Middle Earth would become arguably the most famous story of the 20th century. As a child, Tolkien had seen the world transformed by the Industrial Revolution. As a young man he had survived the brutalities of the Great War, the first conflict to engulf the whole world. And from these twin experiences, Tolkien would create what he considered to be a new mythology for the modern world.

Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings chronicles the twilight of the Third Age of Middle Earth, and the battle to defeat the dark lord Sauron by destroying the One Ring, a quest which can only be fulfilled by the hobbit Frodo Baggins, a hero defined by the purity of his spirit rather than his physical strength. Should he fail, the pastoral world of Middle Earth would be overrun by evil, and turned from green fields in to smoke belching factories.

George Orwell was only a decade younger than Tolkien, a product of the same culture and upbringing. Nineteen-Eighty Four- Orwell’s masterpiece of totalitarian horror – is at least cosmetically a very different book to Lord of the Rings. It encompasses the world of Oceania, an all-powerful, totalitarian state. The story follows Winston Smith, a low ranking bureaucrat attempting to find personal liberation and space to love Julia, a young woman also trapped within the state. But unlike the heroes of myth, Winston Smith’s attempt to overcome the oppressive regime of Big Brother ends is absolute failure. He is tortured in room 101, forced to betray his lover, and left a broken man. Nineteen Eighty-Four shows us a world utterly crushed beneath the jackboot of totalitarianism, with no hope for redemption.

As different as they may appear, the stories of Orwell and Tolkien are both products of imaginations trained by similar cultural experiences. They both encompass worlds, and the fates of those worlds and in doing so, they reveal aspects of our own world. The oppressive power of Big Brother in Nineteen-Eighty Four and of the dark lord Sauron in Lord of the Rings are both reflections of the very real oppressive powers that challenge the wholeness of our world in reality. And like thousands of great science fiction stories, from those of Asimov and Le Guin to the masters of the form today, they use the imagination to show us our world as we could never otherwise see it.

The Re-emergence of Imagination

Science fiction has grown from its origins on the printed page. In films, television, comics and other narrative media, science fiction stories are a cornerstone of popular entertainment. Star Wars. The Terminator. Harry Potter. The Hunger Games. The Matrix, too, is often dismissed as simple escapist entertainment, but the success of science fiction and fantasy stories represents the re-emergence of the imagination in our world of reason. Through the mass media science fiction is now reaching global audiences, and helping us to understand our world from the planetary perspective.

Contemporary science fiction weaves ever more sophisticated visions of our planetary future. Charles Stross’ Accelerando follows three generations of one family into the future as Earth is transformed by the “technological singularity”, the point at which change driven by technology outstrips the human ability to comprehend it. A point, some might argue, we have already reached. Zoo City by Lauren Beukes explores an alternative future Johannesberg where an underclass of criminals are stigmatized by being “animaled”, magically bonded to an animal familiar. Beuke’s planetary vision is distinctive for escaping the assumptions of the technologically developed first world, and extrapolating instead a future through the lens of the world’s emerging economies. The baroque fantastical visions of China Mieville in books such as Perdido Street Station, The City and The City and Embassytown reform many of science fiction’s earlier visions, from the fantasy world building of J.R.R. Tolkien to the space opera stories of Issac Asimov. Mieville’s planetary visions undermine those which have come before, challenging us to ask if we can ever understand the reality in which we find ourselves.

The wider message of science fiction isn’t necessarily the content, but rather, the medium itself. If science fiction is the great product of the modern imagination, then it is to the imagination that it directs our attention. Today our relationship with imagination is increasingly complex. We value the products and innovations that drive every aspect of modern society, even while we continue to underestimate the imagination as the source of those things. We remain in the Enlightenment paradigm, alienated from our imagination, treating it as little more than an avenue for idle entertainment and desperate escapism.

But for generations our stories have called us back to the imagination as a source of insight and understanding. J.R.R. Tolkien, Ursula Le Guin, Issac Asimov, George Orwell, Lauren Beukes, China Mieville and thousands of other creators of science fiction offer us powerful and potent visions drawn from the imagination. If there is one single message we should take from science fiction, it is that the imagination has an unspeakably important role to play in solving the problems of our world. We can analyze the physical, social, cognitive and cosmic systems of the world in the finest detail. But it is only through the imagination that we can begin to synthesize that knowledge back into a whole. And from that informed imagination comes the planetary visions of science fiction. If we wish to solve shape our “Blue Marble” planet in to a better world, we may do well to pay attention to them.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Isaac Asimov – Foundation

Lauren Beukes – Zoo City

John Clute – “Fantastika and the World Storm”

Frank Herbert – Dune

Ursula K. LeGuin – The Lathe of Heaven

China Mieville – Embassytown, Perdido Street Station, The City and The City

George Orwell – Nineteen Eighty-Four

Mary Shelley – Frankenstein : A Modern Prometheus

Charles Stross – Accelerando

J.R.R. Tolkien – Lord of the Rings

Jules Verne – Around the World in Eighty Days, From the Earth to the Moon

Another fascinating discussion. I agree that science fiction has often been a prompt for science. My new book looks at the rocketeers who built machines to take us to the moon. The space travel theorists they looked to were inspired directly by novelists. The Russian Tsiolkovsky developed his papers directly in response to the detailed visions of Jules Verne. Werner von Braun soaked up the stories of Verne, HG Wells and others as a child. And as science fiction emerged into film, ideas from movies like Fritz Lang’s ‘Frau Im Mond’ and later Kubrick’s ‘2001 Space Odyssey’ fed back into the Space Programme in one of those feedback loops of imagination and curiosity, without which the lunar race was an impossibility. My book starts with: ‘long before hydrazine or aluminium were invented, imagination was our first rocket.’ Science, in positing hypotheses about the nature of the world, begins with the same impulse. I like to see what happens when science and story and poetry collide. Your wide-ranging survey of these relationships was spot on.

LikeLike

Thanks Siobhan. I hope you’ll let me read your book at some point.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Good essay. However… Nineteen Eighty-four isn’t a book without hope, despite appearances. If you get a chance have a look at the appendix on newspeak at the back. I’m referring to the tense it’s written in. And, unlike the appendices in LOTR, it’s not written in the author’s voice. Winston was right about the proles.

LikeLike

That’s interesting. It would be hard, maybe impossible, for Orwell to write such a bleak story without engineering some hope as well.

LikeLiked by 1 person

very nice. love from the 021

LikeLike

Reblogged this on markovegano and commented:

I thought it was already doing this.

LikeLike

Is there any decent contemporary science fiction now? I notice that most of the writers that you mention are from decades ago, during the golden age of the genre.

I stopped reading most sci-fi back in the 1980s, when there was an abrupt veer toward fantasy, or the constant rehashing of Star Trek and Star Wars on the shelves of the booksellers. I enjoy Neal Stephenson and Larry Niven the most, but rarely see anything of that caliber anymore.

LikeLike

Sure, there are authors in the Niven / Stephenson mould. But like all things it changes over time.

LikeLike

I’m writing a science-fiction novel, self-publishing in 2016. Wish me luck. This is all inspiring for the likes of me. Blessings and Peace!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I hope it goes well for you!

LikeLike

Thanks Bro! I needed that. Have a good one!

LikeLike

ABSOFUCKING LUTELY … ENGINEERS CANNOT DREAM OR IMAGINE WORTH SHIT BUT YOU PLACE YOUR IMAGINATION IN FRONT OF AN ENGINEER >>> NEXT THING YOU KNOW IT EXISTS >>> ASK FOUR MIT ENGINEERS FOR A MOFO DYSON SPHERE AND THE NEXT THING YOU KNOW THEY GET RIGHT TO WORK … STAR TREK THE IPAD … ITS SCIE FI THAT LEADS ENGINEERS BECAUSE TO BE AN ENGINEER IS TO INHERENTLY WORK WITHIN THE LAWS OF PHYSICS >>> I HAVE LESS OF THAT TO WORRY ABOUT …

LikeLike

YES I AGREE ;)

LikeLike

My own sci-fi novel Reborn City could be considered an attempt at creating a slightly better world. I’m not sure if it can change the world, but I hope it might help to deal with problems of Islamaphobia, racism, and other ills that plague our society. Thanks for the article.

LikeLike

There’s a whole other essay on utopianism I think!

LikeLike

I might have to check that one out.

LikeLike

Story makers explore ideas, that often manifest later. A scifi writer called Edward Bellamy predicted a society 100 years later, predicted correctly credit cards and music on demand.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Looking_Backward

LikeLike

I’d forgotten all about Bellamy! Will take a look.

LikeLike

Very interesting article. This is the first article I have read by you, Mr. Walter, but I hope to read more. I think that you are absolutely right: the reemergence of imaginative fiction is amply apparent in that old maxim about people voting with their feet. The movie industry (though fraught with much ineptitude/shallowness) has brought such stories from being a fringe interest group to mainstream popularity.

If interested, I would welcome feedback on my own blog which I just recently launched that features a serialized story: “Jury Selection.”

LikeLike

That’s certainly true. In mass media now, imagination is the mainstream.

LikeLike

This is a great synopsis of science fiction literary history!

LikeLike

On the issue of incompatibility between art, science and religion, it might be true for the first two, as the first usually dismisses the second as an appeal to ignorance fallacy, while the second rejects major theories of the first (Evolution, the Big Bang etc…). I think art and science can cohabitate beautifully. Science is a huge source of inspiration for artists (Isaac Asimov was a scientist, for example) while the products of our imagination sometimes drives scientific progress, as you clearly demonstrate in your post.

Congrats for the awesome (literally) post. First time I stumble on your little corner of the blogosphere, but this makes me wanna read more!

LikeLike

Congratulations on being Freshly Pressed.

LikeLike

Loved it. The re-emergence of science fiction and its slowly growing social acceptance is only good for both imagination and our future as a global rather than individual society. What I find interesting is the acceptance of science fiction on the YA scale, perhaps cutting out some of the world building, but creating a viable stepping stone opportunity. And of course you’re right, we could all use a little more hope and imagination.

LikeLike

Its a great article. I would make the observation that the very imagination that you find aspirational can also be a mental shackle as well as a guide. Are all women in mini-skirts in the future? Why is human development so linked to taking drugs as shortcuts? etc. There are many examples where science fiction as a genre has held us back in framing how we think of the future.

Also, I would suggest that it’s not that we’re experiencing a re-emergence of imagination; we’re experiencing a reconnection with mythic forms of storytelling.

The examples you reference: Star Wars, The Terminator, Harry Potter, The Hunger Games, The Matrix are all based on mythic narratives that are part of the cognitive collective. This is a psychological function – we’re always been imaginative. The driver of this is a form of postmodern psychology, we think in more narrative forms.

To your starting point about the blue marble, the best bits of imagination is serendipity. In our curiosity and imagination to see what was at the moon, the most amazing and unexpected thing of the journey was the view of our home and place in the cosmos. Thanks for the article.

LikeLike

Great comment, thank you. I recognise the mythic narrative direction and am fascinated by it.

LikeLike

Congrats on FP’d!! Great post.

LikeLike

NICE!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

LikeLike

air to the throne

during the great gathering on mars in 2718, the fate of earth was decided in a game of rock paper scissors. the interplanetary delegates assembled had been in talks for days prior to the final clinch fisted blow. eson, son of jam, was at the time the most respected interplanetary explorer and the long standing ambassador of earth to the furthest galaxies. to humans he was was the invisible ether that bound entire systems together by his very name. such was the power of eson, son of jam. when the final fist had fallen, eson, son of jam, stood victorious, but not relishing in his victory, he took to his knee, bowed his head and said “to none…but all…forever”. these words marked the end of a love story in the solar season. earth was evacuated under a new intergalactic treaty and declared an h-free system. for the next 10 000 years, no human being would inhabit the earth, all other lifeforms would be left to flourish by the will of time and any manner of structure or system would remain as they lay. religion’s final tombstone…laid to rest

jwm

LikeLike

Great post.

I am a big Jules Verne fan, and agree with your observation. I think of people like Captain Nemo and Phineas Fogg, who were pioneers in their respective fields of interest. They captured the imaginations of millions and encouraged people to think out of the box and not settle for mediocrity.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Sci-Fi is definitely a nice way to use to subtly suggest future technology. I do however believe that to really achieve most of those magnificent devices and gadgets waved around and used the entire human race should start to put away our differences and start focusing on improving everybody else’s education and standard of life in order to provide the scientists of the future with the opportunity to invent and discover the technology that we need to achive our technological dreams … Great Post !

LikeLike

Love this: “…science also suffers from its own fundamentalism; a materialist philosophy that rejects all internal experience as invalid, meaning that art of all kinds is also devalued and pushed aside.”

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Sally Ember, Ed.D. and commented:

Love this: “…science also suffers from its own fundamentalism; a materialist philosophy that rejects all internal experience as invalid, meaning that art of all kinds is also devalued and pushed aside.”

LikeLike

It would be amazing to live in a sci-fi world:

Check out advice at glittergear.wordpress.com

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Liturgical Credo and commented:

Good insights into science fiction and creative imagination, with special reference to George Orwell, J.R.R. Tolkien, Ursula Le Guin, and Issac Asimov.

LikeLike

You do raise an interesting point, Scifi and fantasy especially the good ones are just another way of dealing with philosophical stories. Dune, has the struggles between religion (bene gesserit), political power (the emperor) and economic power (The guild). Lord of the rings was in a ways a reflection of how Tolkien viewed the changing English society at the time. Thank you for your insight.

LikeLike

This is a wonderful article. Sadly I haven’t read most of the books or authors you mention. I’ve read 1984, of course, and seen the LOTR movies. I read Leguin’s novel, The Dispossessed, years ago and it blew my mind. I think science fiction can open our minds to new perspectives like no other genre can. Often it reveals the need for change in our present society through stories in other societies centuries and light years away. Not to mention it can be wicked funny and bizarre, which is refreshing if the world has been boring you. Someone, somewhere, said one time, “It will be possible for everything in creation to be uninteresting, except people. When all else fails, human beings will always find a way to surprise you.” And isn’t that what sci-fi is ultimately about, humanity?

LikeLike

I agree wholeheartedly! Imagination, the ability to sit and imagine new ideas, concepts, ways of thinking, new worlds, new dimensions. Surely there is no clear distinction between the enlightened and fantastical versions you have mentioned as they stem from the same source; imagination?

I grew up following sci-fi, particularly Star Trek. It introduced me to the wonder and exploration of galaxies, cosmology, physics, inter-species diplomacy and tolerance. As well as the drama and action. But it also provides an amazing blue-print for a potentially better way of life for humans. War, poverty, tyrannical regimes/systems have all been eradicated on earth. Our purpose is to work to better ourselves and our humanity.

Imagination created that vision. And now we are planning manned missions to mars!

LikeLike

I say yes! So many inventions are fueled by the imagination.

LikeLike

Great post, well done. I believe that Science Fiction can help us create a new future, a new universe. After all, there’s no reason why the science fiction of today is not the science fact of tomorrow. I wrote a post as a tribute to one of the fathers of Science Fiction – Percy Greg ( http://wp.me/p4L5j9-5j ) but at its core it was about the hope, the dreams & the inspiration that Science Fiction & Fantasy writers give to the world as their legacy. Who knows where the current crop of these writers will lead us….to infinity & beyond!

LikeLike

This is a fantastic. As a huge fan of the sci-fi and fantasy genres, I find this to be a very good literary summary! George Orwell is one of my favourite authors, and I’ve read works by J.R.R. Tolkien and Ursula Le Guin as well. So many of today’s inventions were “predicted” by past writers, so I wouldn’t be surprised if our future lies there as well.

Thanks for this awesome read!

LikeLike

Yes

LikeLike

EXCELLENT. This validates every manuscript I have ever written, all 336 of them.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on the bridge & the gap and commented:

So not only am I a spirituality seeker, but also a science fiction writer. Some of my all time favorite stories include very grounded and relate-able characters in a beautifully unique world that lives within our imaginations. Science fiction is becoming bigger and bigger in the entertainment world, so stay ahead of the curve! Keep science fiction thriving and use it to make the world a place full of imagination and creativity. Everything we love should be because it makes us feel better or is something we can share with others to thrive, grow and learn. Expand your minds to the possibility of a science fiction (or non fiction!) world!

xo

L

LikeLike

Good points – and I agree. For me the issue is as much social as technical. We point to something mentioned (often as a throw-away line or background tech) in old sci-fi, and look for it in today’s ‘advanced’ world. Sometimes we have something similar. But that’s not really what sci-fi is about. I’ve always felt that the genre – of which I have long been an enthusiast – offers a lens on the current world, on the way we think. Epitomised in the popular sense by Roddenberry’s vision of a more socially equitable and – crucially – optimistic future.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on petrichorandpalindromes and commented:

Absolutely fantastic and incredibly well put together.

LikeLike

A damn good read, sir.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on washrinserepeate and commented:

This is an amazing read and great insight into sci-fi not just as entertainment, but as a means for cultural and technological advancement!

LikeLike

Reminded me of this:

LikeLike

Science fiction are one of those things in the childhood that brought me closer towards world of science. That’s a nice article you have written Damien.

Cheers!!1

LikeLike

I don’t see why not. It’s been doing it for decades now. It all started with H.G Wells.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on THE WRITING REALM OF HD and commented:

Awesome post full of awesome literature

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on Signsofanopencity and commented:

I think you bring back the possibility of dialectical culture and it’s inspiring: I went to the Science Fiction course you ran at Nottingham Contemporary in 2010 (I can’t believe that was eight years ago!) and it was prophetic (The Man in the High Castle, for example. What that made me realise is that when you’re connected to some of the important bits of knowledge and information you can share that and change so much. Well done and keep on writing, thinking, researching and taking good care of the things that really matter (in time and space!)

LikeLike