Humans like stories. In fact, it’s fair to say we are obsessed with stories. And never has our society been richer in stories. Today we have access to all the books, films, TV shows and other story media ever made, with more being made all the time.

Little wonder then that novels became a huge cultural success story – the television, movies and video games of their day.

But if you wanted to lose yourself in a story in 17th century England, where did you go? Most likely to the church or to the Bible, to have biblical myths read to you. Or you might read them yourself if you were among literate minority. Theatre of course, in cities or when a troupe travelled on tour. Possibly to a storyteller to hear a folk tale or two, or maybe some some bawdy stories told in drinking holes. But all said and done, your options were somewhat limited.

When novels began to arrive in the 18th century, as the costs of printing decreased, they arrived in to an environment starved and hungry for stories. And they provided stories stories that were far more complex, original and engaging than the competition. Unless you had a very good vicar, it’s unlikely his storytelling held much a candle to the serial fictions of Mr Charles Dickens. Little wonder then that novels became a huge cultural success story – the television, movies and video games of their day.

Novels allowed the telling of more sophisticated stories. And novelists quickly innovated new tools for the telling of stories. Novelistic techniques that we simply take for granted today, such as limited 3rd person point-of-view, simply didn’t exist in the early days of novels. Stories were told either by the writer as omniscient narrator, or through formats like the epistolary ‘novel of letters’ that allowed the characters to speak for themselves. A large part of the work for students on a creative writing course is to learn all of these novelistic techniques, so that they can write novels to the standards expected by readers today.

The film, in its narrative compression, is far more like the short story than the novel.

Examined from a technical perspective, a novel like War & Peace by Leo Tolstoy is an amazing storytelling achievement. It doesn’t simply tell one story but many, weaving through multiple points of view over a timespan of many years. It chronicles major events in human history, and illustrates them through their human dramas. It leads the reader to ask the big philosophical questions that underly the events. What is war? What is peace? How do we best live in either circumstance? There are other comparable literary achievements – Homer for instance, although the Iliad’s poetic form makes it a tough read for most – but the novel made this kind of complex storytelling widespread. And hugely, hugely popular.

Film took the development of story in a different direction. Filmic narratives are highly compressed, simply to fit in to the typical 120 minutes of time a feature film occupies. The film, in its narrative compression, is far more like the short story than the novel. Film also has an immense capacity for spectacle. You aren’t just watching a cowboy story, you’re seeing a real man firing a real gun. In the modern era of CGI, that spectacle has grown to epic proportions. The kind of slow, subtle character development novels thrive on is hard to achieve in film, and rarely tried today, when explosions and superheroes are so much more profitable.

Storytelling on television was hobbled for decades by that medium’s dependence on advertising, and the advertisers demand that television shows appeal to the lowest common denominator. Episodes of television drama were relatively short, sometimes only 20 minutes when advertising was removed. And networks did not allow producers to advance the storyline across episodes. The TV miniseries – often adapted from novels – allowed some great TV drama to be made, in particular shows like I Claudius and Tinker Taylor Soldier Spy in the UK.

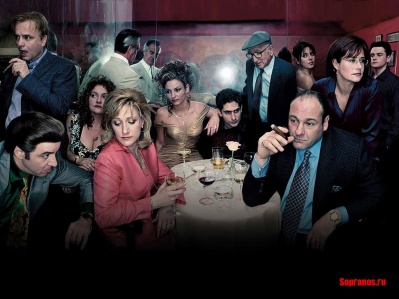

The HBO “box set” series is designed to be sold directly to the audience (as opposed to attracting advertisers) and consequentially aims for a far higher standard of narrative. It typically gives 10 hours of screen time in 1 hour chunks dedicated to telling one coherent story. Each 1 hour episode has its own discrete plot and subplots, but they all feed in to the over-aching series plot. They feature an ensemble cast of characters – as opposed to the single protagonist of most films – all of whom grow and develop (or die!) as the series unfolds. And they deal with complex human situations and relationships. They are, from many perspectives, highly novelistic. And in all honesty, the best of them leave War & Peace and many other great novels, eating their dust.

The Sopranos. Madmen. Band of Brothers. House of Cards. Game of Thrones. My new favourite, True Detective. Individually the best shows in the HBO format (there are now other producers) are the equal of any stories ever told. And in many regards, better. Taken as a whole, there is a strong argument that they are part of the most amazing flourishing of story in human history. They combine the complexity of novels with the spectacle and film. And they bring another element almost unique to television. They are written collaboratively by teams of writers and script editors. These shows aren’t just the product of one superb imagination, but many of them, working in unison.

The novel, having pioneered the complex high quality storytelling it is clear audiences hunger for, now struggles to match the best of that storytelling in other mediums. Novels can’t touch the spectacle of film or the new king of that hill, video games. And they’re outgunned in the sheer richness of storytelling the best television shows can achieve. Not because the novel can’t match that quality, of course it can, but because doing so is very difficult. And the number of writers capable of producing stories of that quality is very small.

It’s easy to set up shop as a novelist. It’s ridiculously hard to actually write high quality novels. Writing a great novel is an achievement on the scale of making a major scientific breakthrough or winning a significant military battle. That’s why in British history Jane Austen is remembered alongside Isaac Newton and Horatio Nelson. And yet very few writers seem willing to pursue the long, hard path towards that kind of achievement. Absurdly, there’s a common conception among writers that they don’t even need to learn to write before putting their work in to the world. How many scientific breakthroughs are made without decades of learning? How many battles won without years of collective experience being deployed on the battlefield? Why expect making art to be any different?

Among the runaway hits in recent publishing is A Song of Ice and Fire by George R R Martin. It’s a novel in the epic fantasy genre, but its success is far more to do with its complex, high quality story telling than the presence of dragons. Martin was a Hugo award winning sci-fi writer at a young age, who then spent two decades working in the word-mines of Hollywood script development, before bringing all of that expertise together in his masterpiece. The books were already massive bestsellers, head and shulders the best books in their genre, before being picked by HBO, where they required little work to fit in to the new television format.

The response of publishers has been comically absurd. For the best part of a decade now publishers have been flooding their distribution channels with fantasy series in the style of Game of Thrones. But instead of seeking out the few writers who might have the chops to make a new work on the scale of Martin’s epic, publishers have paid peanuts to debut authors to make third rate clones that lack all the technical expertise to equal the original. And this is far from a unique scenario. The publishing industry, instead of nurturing quality writing, has turned itself in to a cloning operation. There are still quality books to be found of course, but they are buried amongst a swill of third rate clones of the rare bestsellers that appear. And this, more than anything else, is destroying the audience for novels. Imagine if HBO, alongside True Detective, also released 200 competing television shows that looked similar but nowhere near as good. They would quickly undermine their audience engagement, just as publishers have. If publishers want their business back, they need to be as obsessed with story quality as HBO.

There’s a bun fight about self publishing in the book trade at the moment. Half the trade are waking up to the reality that self publishing is the future, while the other half are looking for reasons why it shouldn’t be. The number one reason is quality. Self-publishing doesn’t provide a career path for writers, or police quality. But publishers abandoned both these roles long ago. The writers who achieve real quality in their work do so entirely under their own energies. And that small minority of writers are now turning to self publishing as an answer to the serious question, what value are publishers adding if they do not nurture quality? Because, if novels are to thrive as a medium in the 21st century, it is only an obsession with quality that will place them among the best storytelling on offer.

While I agree GOT and House of Cards are compelling offerings for a TV venue, I for one am still far more likely to read vs. watch. There is something about a show, be it movie or TV which makes the watcher captive to the actors’ and director’s personalities, pacing, style. It can be stultifying. It’s like facing a salesman face to face vs. over email. I’ll take email every time :-) A good novel provides the bones for which the reader’s imagination takes flight. It draws the reader in, it enables fantasy to bloom in the mind of the reader by enabling the reader to become the character, to imagine himself or herself in the story. The visual arts provide sensational spectacle but IMO do not invite that same level of engagement as the characters are already fully embodied. Novels, and reading, will live on. Or, dinosaurs such as myself will die out ;-)

LikeLike

I read way more than I watch TV. But I struggle to find books that match the experience of these HBO shows.

LikeLike

They are of course different forms of storytelling, series vs HBO series vs movies vs novels.

In a culture and society where time is a premium, the novel has a real problem versus other forms.

LikeLike

I also read more than I watch TV, but nowadays I find myself enjoying more TV shows than novels. Even comics, a medium in which it should be easier to replicate TV’s better aspects of storytelling, appears too mired in the movies to pull this off. The irony is that, until the 80s, comics used to pull this off way better than the television shows from the same period.

But, back to novels: I guess most authors show a lack of technique, as if they didn’t knew how to properly handle many characters and plots simultaneously. But, out of interest: True Detective was entirely written by one author only (and also Penny Dreadful), instead of a committee like Sopranos et al. Did you find it more engaging than the others, or at least more “authorial”?

LikeLike

I’m watching True Detective now and I think its excellent, and the single author is very clear. I’ve just read all of his available prose this week. He’s a truly remarkable writer, on page and screen. Penny dreadful I haven’t caught up with yet.

LikeLike

More than that, I think, publishing doesn’t really value text. This will sooner or later turn into a blog post in my own blog, but my thought is, publishing values having elements in a book that justify the cover that sells the book, the ad copy that positions it, and the catalogue space that slots it. So writers are pushed to include the “cookies” — the sales points — and very little else, and unfortunately, this is something many writers can do. Doing something well and slipping a few new tropes in and turning the reader to a new view of the world, not so much. Because that can’t be presented in 100 words at the quarterly meeting by a 28 year old MBA in marketing who doesn’t read, and publishing values that person’s opinion more because they talk about selling books, not about loving them.

Or something. More thought required.

LikeLike

All of this John. All of it. there are good people and good teams in publishing. But they seem swamped by the culture of 28 year old MBAs. Perfectly put.

LikeLike

Don’t forget video games! I genuinely believe that video games are going through a narrative revolution at the moment. The Last of Us has better dialogue (and, even, performances), and a vastly more original and moving plot than any TV- of novel-based examples of the post-apocalyptic genre I can think of in recent years. BioShock: Infinite has a more creative SF-nal setting (and ending, though flawed) than any Science Fiction book I’ve read since China Mieville burst onto the scene, and the guys behind Assassin’s Creed, though not great writers on a sentence-by-sentence level, have stumbled upon a narrative premise that’s allowing them to create an immensely complex, centuries-spanning historical epic that’s weaving real events with fictional historical revisionisms and metafictions in a fascinating way. Assassin’s Creed has also given us Islamic main characters, a black French former-slave protagonist, an old man falling in love, and a native American of mixed heritage… so much more diverse and interesting than much of what novelistic mainstream genre fiction publishers seem comfortable with today.

And then more avant-garde, independent games like You Were Made for Loneliness, To the Moon, Bastion, Gone Home, Transistor, Journey and Limbo, or even Child of Light (a video game that’s entirely written in split rhyming couplets (ababab etc)), are doing incredible things with ideas about reception theory, minimalist language and experiments with the ways in which the player(user) is complicit in creating the narrative.

I think I’m more excited about video games’ potential than either T.V. or novels at the moment (which is a strange revelation for me, as I always consider myself a reader first and foremost). But the recent emergence or video game auteurs like Ken Levine, Neil Druckman, Amy Hennig, Todd Howard etc. is pushing things in great new directions. My message to narrative critics at the moment is: ignore video games at your peril. Just like those who dismissed comics as a depthless dalliance, I wonder if those who say the same about video games will soon find themselves left behind?

LikeLike

Darn it, there’s an ‘of’ in there that should be an ‘or’, and an ‘or’ that should be an ‘of’.

Apologies.

LikeLike

I agree that the best TV is at least equalling what’s going on in books, and both writers and publishers need to think about where that leaves them. In this, as in so much else, fear of change seems to be driving many responses. But change always happens, and it’s happening ever faster in the industries that support/use story telling. What works now won’t work in ten years time, and the successes aren’t going to be people who follow a particular path now, but those who learn to keep adapting.

LikeLike

Change is fast in storytelling because it also has fashions. Fantasy is in this year, it won’t be next.

LikeLike

I don’t own a TV, so I read mostly. I have a projector and a computer thugh, so I follow some of the HBO-series and watch movies too. What I’d like to add is that some of the really good stories are made for RPG’s like Skyrim and others. They aren’t always very well written, but man, they do have plot.

LikeLike

Have to admit I did enjoy fighting the dragons in Skyrim.

LikeLike

Some very interesting points. Storytelling aside, I’d say that the experience of watching something (T.V., movies), versus making some choices in a controlled environment (computer games) versus reading (no choices, but the narrative unfolds entirely in your head) are to some extent different experiences. Part of the struggle with novels is that they’re a little bit harder to absorb than material you watch, or material that’s seeded power-ups of one kind or another to keep you seeking, and we’re inundated with those easy choices, where we have to seek out novels.

That said, I think you’re spot on about the publishing industry not fostering quality (or rather, seeing it as something that’s great if you can get it, but not a driver). I’ll probably ultimately self-publish (I’m still outlining the next novel I intend to write), and though there are multiple reasons for this, among them is my desire to conceptualize my audience as readers/myself, i.e. write the kind of work I want to read, and believe that a niche of readers are out there, as opposed to tweaking my work 25% for editors and publishers, in the hopes that I’ll end up mainstream published (which is percentage-wise unlikely, and brings with it rewards that may or may not ultimately compare favorably to self-publishing).

LikeLike

That raises a remarkably important factor – the extent to which seeking mainstream publication distorts the writers work. And crucially, guides the writer away from the niche audience that is naturally their own, to a mainstream audience they may never satisfy. Or that may simply not exist.

LikeLike

As an aside to that comment, one thing that always rubs me the wrong way are agents and editors confusing advice about writing with advice about how to write so that agents and editors will accept your work.

A great example of this is the whole “if you haven’t captured your reader by the first page, it’s over” type advice. I know as a reader, I’ve got at least 10-20 pages in me before I give up, and I’ve got no problem with confusing or even fairly static first pages, especially if the writing is good. That kind of advice is about hooking agents/editors, not readers, but it’s often given as “writing advice.”

LikeLike

Which is one reason why mainstream publishers will continue towards irrelevancy. The online exchange of information breaks the old paradigm of ‘we know what’s good to read’ – publishers were built on an info-scarce society, thus their curation and marketing of talent was a value-add. That world is behind us. I find all my new reads on twitter & wordpress by following people who interest me, then reading the first 5 pages of their work on B&N.com or Amazon. This approach bypasses marketing channels.

And, BTW, the arguments WRT publishing affecting the writer’s focus as well as following ‘cookies’ of popularity applies as well to movies or TV.

LikeLike

Capture your reader in the first paragraph.

If you can’t do that, you don’t have reason to be writing.

(Yes, you’ll give folks some margin, but they should aim HIGH not low).

LikeLike

Pathaydenjones, I think you’ve hit the nail on the head: I read an article a while ago about Amazon changing the game and I think it still stands: in a world with lots of information/material, it opens the door for niche markets, i.e. a novelist doesn’t need to appeal to 5% of a broad population, he/she needs to connect with enough readers that are interested. To put it another way,there might be 50,000 people in the world that are passionate about your work, but that’s (way) more than enough if you can get to them, and make a decent margin.

LikeLike

Steven I hope you are right as I am certainly breaking some of the ‘rules.’

LikeLike

“The publishing industry, instead of nurturing quality writing, has turned itself in to a cloning operation. There are still quality books to be found of course, but they are buried amongst a swill of third rate clones of the rare bestsellers that appear. And this, more than anything else, is destroying the audience for novels. Imagine if HBO, alongside True Detective, also released 200 competing television shows that looked similar but nowhere near as good. They would quickly undermine their audience engagement, just as publishers have. If publishers want their business back, they need to be as obsessed with story quality as HBO.”

How is this different than any other industry, at any point in the recent past? You get something both of quality and popularity and suddenly you have a thousand imitations seeking to cash in. Hollywood has been like this for decades. The tech industry is no different. Videogames, I assure you, are no different. Look at the number of sitcoms each network produces. These sitcoms are pretty identical, the show setup and the jokes are recycled constantly. Compare the number of sitcoms with the number of Hit ones. Just look at the amount of shows on TV on our millions of channels vs the ones that are of renowned quality.

Do you honestly think that only recently publishers have abandoned quality? Every industry, including books, produces a lot of crap. Hell, many authors’ first books are indeed crap. They get better.

Quality floats to the top, regardless of how much crap is out there. Because fans talk.

I was at a convention talking to a self-published author who sold 20,000 copies of his books in the span of 3 months Before a traditional press picked him up. I asked him, “With so many self-pubs out there, with little marketing on your side, how do you get noticed?” He said, “You either catch lightning in a bottle, or you put out a damn good book, then you put out a second damn good book., then you put out a third damn good book. Word of mouth will do the rest.”

You yourself point out Martin produced his great book after decades of work. He had to build up to that quality. So, the next Martin isn’t going to pop that sucker out without the same amount of work. Therefore, the future Martins of the world will continue to produce until they can smith such an epic. And when they do, people will notice. Not only because the book is of grand quality, but the decades that author has been producing has built up a fanbase who will explode.

LikeLike

The fact that other industries have this problem does not mean it is not a problem. The scale of the problem is massive in publishing because bar for entry is low.

LikeLike

Also, there’s one point everyone in the Traditional Pub vs. Self-Pub discussion seem to always forget:

Small press.

LikeLike

The small press are effectively dead. Whatever niche they fulfilled before Amazon is filled by the fact any author can do this for themselves.

LikeLike

Well…what about something like NESFA Press or Subterranean Press, Damien?

LikeLike

The deluxe presses, yes. That’s a specialist market they can hold on to. What I’m thrown by is debut authors signing trad publishing deals with small presses for 15% commission. It’s very close to the trick vanity publishers play, playing on the fact amny writers don’t know the worth of the services provided.

LikeLike

You do realize that just because anyone can epub, not everyone will, or even wants to, right?

If you epub, you have to edit it yourself, format it yourself, typeset it yourself, handle the cover yourself, and handling the marketing all by yourself. If you want it sold at conventions, you are the only one who is going to be sitting there selling it. Epubing means you’re the only one who is responsible for that book.

For a lot of writers, that’s too much work. For many writers they’d rather be writing, period, and hate that they even have to market their stuff. The rest that i just listed is tedious BS.

I sure as hell am not going to epub for this very reason. I want another set of eyes on the editing. I’m not going to bother learning formatting and typesetting. I have four books through a small press, they go to ten conventions a year, have another publisher who distributes to the cons they don’t go to, and handle international distribution. I can only make one con a year if I’m lucky. In a niche market where most sales are at conventions, that means I’m making nine times the sales than I would.

And as popular as ebooks are, they are not the end and the beginning of all things. Some people legitimately want or prefer a physical book. And if you want your work in a physical book, then either you have to print it and then handle the shipping yourself, or you let someone else do it. The small press is all too willing for that.

LikeLike

You’re welcome to hand all those tasks to a small press, but you’ll pay well over the odds for them. Why hand over your rights to a small organisation with no reach? That’s the problem for small presses.

LikeLike

One of the problems is the publishes are focusing on the wrong customers. They’re not looking for readers to buy books; they’re trying to sell to the book sellers. The other is that publishing is very risky. They may publish a book by a big name author and it tanks, like the book that followed Cold Mountain. They keep looking for the sure thing, and unfortunately, taking chances is really what they need to do to build stock. What’s going to happen when these writers start dying off?

LikeLike

“Self-publishing doesn’t provide a career path for writers, or police quality. But publishers abandoned both these roles long ago.” Damien–it pains me that you continue to be so willingly obtuse and ignorant about the publishing world. Your perpetuation of out-and-out lies is depressing. – JeffV

LikeLike

Jeff, it’s good you feel the system is working for you. If you want to express your opinion on that here, please do so without the invective.

LikeLike

I know for myself, I draw a distinction (in my mind, I’m no expert) between presses that are an integral part of the SFF community and larger, mainstream publishing houses. I think that on the ground, all the individuals involved want quality and good story telling, but it gets hard when there’s a lot of financial pressures to deal with, which becomes more and more of an issue the larger the company is (this is my way of amending my earlier statement about publishers not supporting quality, which is part of a larger discussion about big publishers and the kind of writing they seem to encourage, agents, editors, and blah blah blah).

I know for myself, I’d be happy to receive guidance/support from a press like Angry Robot or Orbit – it’s just that there are so many hurdles to get there that are based on specific individuals really liking your work, it’s easier to focus on something I can make happen, rather than something that seems like more of a dice roll. When I get there, I’ll roll the dice, I’m just a lot less likely than I used to be to put my work on a shelf if I don’t get a seven within a few throws.

LikeLike

One of my critique partners once sent me a link to a website that horrified me. It was all about quantity over quality–that if a self-published author puts out X amount of sub-standard books, even if they suck, a certain amount of unfortunate people are going to buy those books. Multiply that by X, and you have your profit–so, the site said, put out as many books as possible. Eek!! I’m on the complete opposite side of the spectrum–which isn’t necessarily good because it can become a creative block–but I’m so obsessed with quality that I lose count of revisions and go on for two years or more working on a single book. I can’t imagine (or actually, I can, and I’m reeling!) working so hard to get something maybe possibly “good” out there…only for it to drown in a sea of “eh” or just plain “bad” books. Sigh.

LikeLike

Worth looking at the Dunning Kruger effect. Psychological pattern that makes the unskilled think they are great, and the skilled doubt themselves. Either end is equally destructive for a writer.

LikeLike

I am reading about this now and find it fascinating. Thank you. :)

LikeLike

Michelle, you’re in a different pond, and you would be even if every traditional publisher went belly up. The high-speed makers of Processed Book-Like Product are selling almost entirely to each other and in quantities of dozens, not hundreds; readers in general are bright enough to move on and keep looking elsewhere after finding those circles of people taking in each others’ laundry.

The process of discovery remains a problem; I’ve been almost-discovered by a wider readership several times in the course oif 31 commercial books, but I’m still basically a coterie writer (for several different coteries, so that I have to kind of skate around among them, trying not to neglect anyone too long). Traditional pub industry can’t do real marketing because the research on which it must rest is far too expensive, so they settle for the toxic-to-the-new environment Damien and I are talking about. But nothing about the present situation is stable or even likely to stabilize; someone will figure something new out every few months from here into the foreseeable.

Just keep writing good and when you think about selling, figure some large part of whatever you know probably recently changed.

LikeLike

Lol–thank you. :) Guess I’ll go on writing for myself for now and hope I find myself in others when I reach the unforeseeable future.

LikeLike

Whether it’s a blessing or a curse, you pretty much have to write for yourself; you are the only person in the world who cannot avoid knowing what you’ve written, and anyway when people try to write entirely to a market or editor’s demand, the usual experience is that the muse goes on strike. There’s a trace of hope if you write for yourself; otherwise it’s just like having homework every day.

LikeLike