Awakening To The New Real

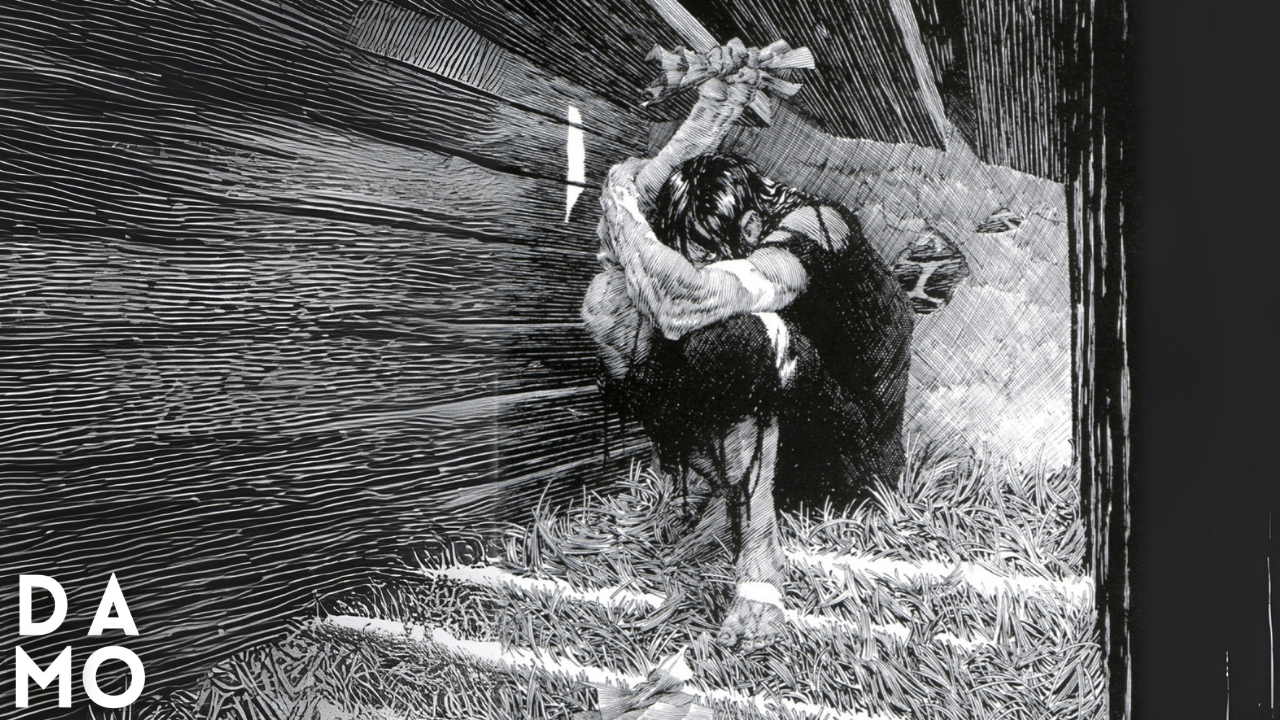

The stench of lightning and charred flesh fills the air. You open your eyes to agony in a body stitched together, organs, ribs and limbs, from the bodies of the dead.

You stagger to life with one question burning in your mind.

A question that will launch you into the world on a journey of crime, murder, and destruction in a desperate quest for your creator.

You are not a human born. You are not a child of God. You are a creature. You are Frankenstein’s creature.

But who are you?

Watch the full video essay on the Science Fiction channel

The iconic image from Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley’s Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus (1818), has echoed across two centuries of literature, theatre, film, and philosophy.

Written as a gothic horror tale, Frankenstein is perhaps the first true myth of the scientific age. The first novel to capture the new reality being revealed by science. The first complete work of science fiction.

The reality that Frankenstein’s creation awakens to on that mortuary slab was the new reality all humanity was awakening to.

Humans had believed we were eternal souls. Creations of God, made in God’s image.

Now science was showing us that we were biological organisms. Products of blind evolution. Machines of flesh and blood.

The horror of Frankenstein is the horror of that awakening.

We’re All Going On A Goth Summer Holiday

The year is 1816—the so-called “year without a summer,” when volcanic ash from Mount Tambora plunged Europe into a strange gothic summer.

In a villa by Lake Geneva, four young artists passed stormy nights telling ghost stories.

Imagine Lord George Gordon Byron, Percy Bysshe Shelley and John Polidori (who would in the same holiday invent the literary vampire)

as the instrumentalists of a New Romantic 80s goth band.

And picture 19-year-old Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley as their lead singer.

It’s a better picture of the energy and spirit of these young artists than the staid portraits we typically see them through.

All three men would be dead within a handful of years. Live fast, die young, leave an immortal literary legacy.

Mary lived on, raised a son, wrote other significant works including The Last Man.

The first scifi post-apocalypse novel, of a 21st century ravaged by global plague and climate change.

But Frankenstein outlived them all

Encouraged by Byron’s challenge to “write a ghost story,” Mary conceived a tale that fused gothic imagery with cutting-edge science. Her influences included Luigi Galvani’s experiments in electricity, Erasmus Darwin’s speculations about spontaneous generation, and the Romantic debates about human nature. The story became Frankenstein, subtitled “The Modern Prometheus.”

Prometheus, who stole fire from the gods, is the archetypal figure of overreaching knowledge. By linking her scientist Victor Frankenstein with Prometheus, Shelley immediately positioned the novel not just as a tale of horror, or a simple a parable of human ambition

but as a myth for the age of science.

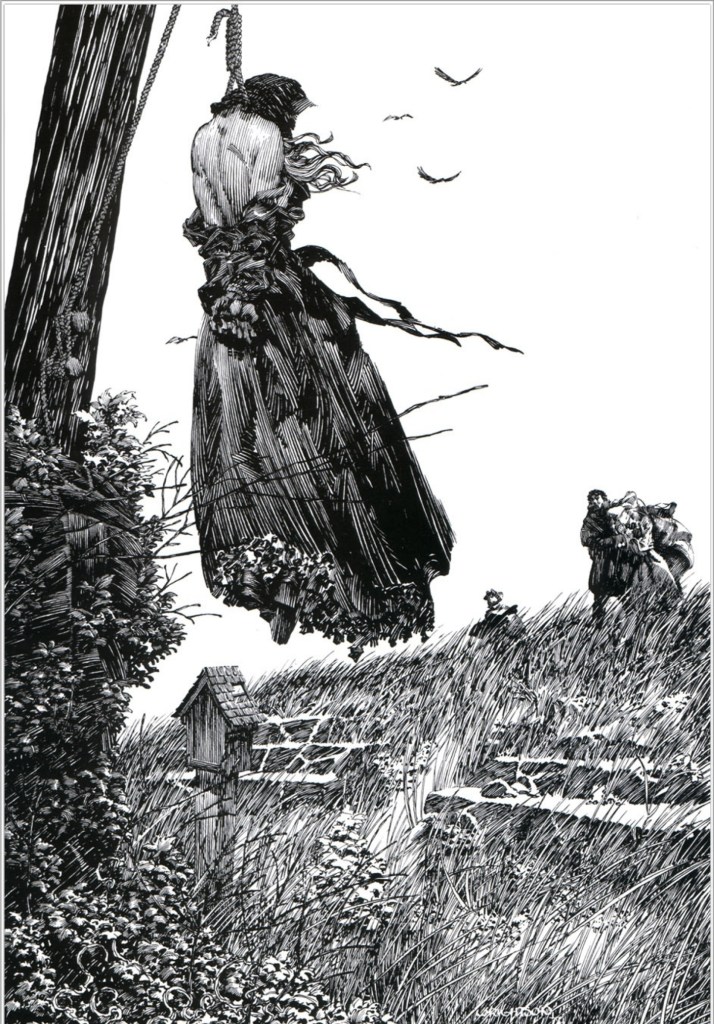

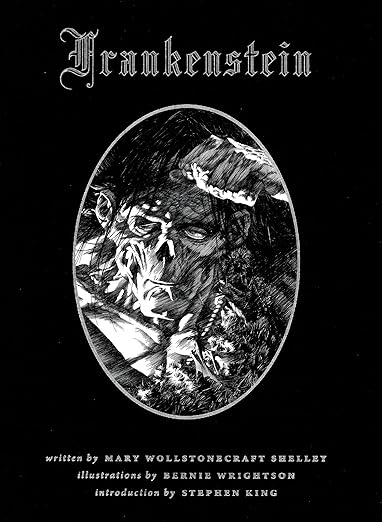

Bernie Wrightson’s illustrated Frankenstein is amazing and beautiful, and also very rare and expensive!

At its core, Frankenstein asks:

Who am I?

What are we? What is it to be human?

The Creature is a homunculus of other men’s bodies. He is a biological machine.

But he is also articulate, intelligent, and sensitive. His “monstrosity” lies not in his monstrous origins, but in the fact that they force all those who see him to see the truth of all human life.

That we are meat machines.

Mary Shelley’s mother, Mary Wollstonecraft, was a pioneering feminist. William Godwin, her father, a radical philosopher. Their daughter was raised in the intellectual hotbed of early 19th century London and exposed to the cutting edge of science and the arts.

Fusing both into the first great science fiction novel.

#

The argument about Frankenstein as THE first science fiction novel breaks in a few different directions.

The case is made at length by Brian Aldiss in his history of science fiction, Billion Year Spree.

Some will point to much earlier writings like Lucian of Samosota’s True Story, which include elements like space travel

Or to works from the early age of science such as Somnium by Johannes Kepler

Others will push the date backwards to Jules Verne or HG Wells

You’ll also find some people claim Percy Shelley, Mary’s renowned poet husband, as the true author. But we have Mary’s original manuscript at Oxford’s Bodleian library, can see that Percy’s contributions were those of an editor, not author or even co-author.

So. Frankenstein is the first science fiction novel because Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley does something that had not been done before. She is writing for people whose world is being turned upside down

by science.

And she creates a new symbol, a new myth for the age of science, to make sense of the change.

The creature of Frankenstein.

Man as Machine

Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley wrote at a moment when science was radically reshaping human self-understanding.

In astronomy the discovery of infrared radiation and spectroscopy were making man ever smaller in an ever vaster universe

Microscopy was revealing the cellular, mechanical, material reality of all life, humans included

Galvani’s experiments on frogs legs had shown that the animal body was animated not by spirit, but by electricity.

Industrial revolution imagery—factories, machines, engines—invited parallels between the human and the machine.

Mary’s great insight was to imagine the human body as a kind of machine that might be taken apart, reassembled, rebooted.

This leap of imagination from the science of her time is what makes Frankenstein not just the first science fiction novel: but the first mythic image for the age of science.

As the myth of Frankenstein grew, it replaced our image of man with the image of man-as-machine.

Almost immediately, Frankenstein escaped the page. Stage plays in the 1820s turned the Creature into a mute, lumbering brute—a distortion that still shapes popular imagination.

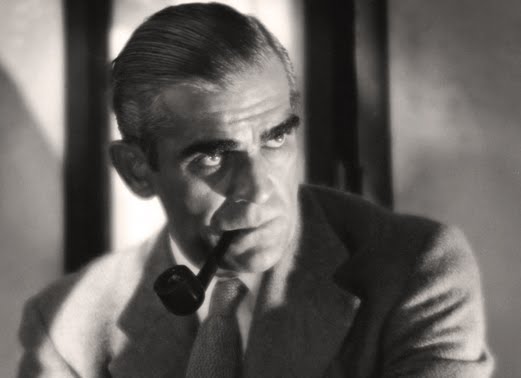

The definitive leap into modern myth came with James Whale’s Frankenstein (1931). Boris Karloff’s square-headed monster, with neck bolts and a childlike demeanor, became one of cinema’s most enduring images. Whale’s sequel Bride of Frankenstein (1935) added irony, pathos, and camp, cementing the Creature as a cultural icon.

In the 1950s–70s, Britain’s Hammer Studios re-imagined Frankenstein with Christopher Lee and Peter Cushing, emphasizing gore and moral corruption. Later films like Young Frankenstein (1974) parodied the tale, further trivialising the Monster.

Frankenstein’s creature became ever more a cartoon monster. A figure of fun and ridicule, even making a sitcom appearance as Herman Munster.

The image of the Creature has been so far degraded that reviewers have slated Guillermo del Torro’s 2025 adaptation for not being horrific

Because it’s a faithful adaptation of the book, that these reviewers have clearly never read

So the real legacy of Frankenstein is carried by its spiritual descendants. Ridley Scott’s cinematic masterpiece Blade Runner. The inhuman beauty of Ghost in the Shell, Ex Machina, Westworld

And many more scifi myths that show us the human in the machine, the machine in human.

Who is the monster?

In Frankenstein, the Creature asks his maker, “Why did you form a monster so hideous that even you turned from me?”

Pop culture mistakes the monster for Frankenstein. Readers know that Frankenstein is the maker of the monster. And critical thinkers recognise that, no, Frankenstein IS the monster.

By abandoning the life he has created, Frankenstein has committed a monstrous act.

But.

Frankenstein is no more the creator of the creature than your mother or father are your creator. The creation, like all of us, is a creation of this reality.

We all exist in what the philosopher Martin Heidegger called the experience of “thrownness”.

We are all thrown into some set of circumstances, a family, parents, strengths, weaknesses, sicknesses, triumphs.

The only remedy to the nauseating experience of thrownness is to take responsibility for whatever circumstances we are in.

The creature in his desperate pursuit of his creator is acting out our modern denial of that responsibility.

Instead we seek someone, anyone to take the responsibility for us. Mother. Father. Priest. Self-help guru. Political huckster. King. God, ultimately.

The mythic image of the loving Christian God is the ultimate bearer of our responsibility for ourselves.

Frankenstein gives us the mythic image that replaces man as child of God. Man as machine. A mechanism of flesh and blood. Meat puppet.

The individual, alone responsible for our self.

The monster is the human who can’t accept that responsibility

“I have love in me the likes of which you can scarcely imagine and rage the likes of which you would not believe. If I cannot satisfy the one, I will indulge the other.”

Why has Frankenstein survived 200 years when most novels fade into obscurity? Because Shelley did not simply tell a story—she created a myth.

For our age of science.

Just as the Greeks told of Prometheus, or the Hebrews of Adam, modern culture tells of Frankenstein. It is the first true scientific myth: a story born not from divine revelation, but from human speculation and scientific imagination.

As science advances into AI, biotechnology, and planetary engineering, Frankenstein remains blueprint and warning. The question “What have I created?” is the haunting refrain of the 21st century ahead of us.

On the mortuary slab, the Creature opens its eyes. Two hundred years later, we are still staring back.

#

Do you ever wonder why our entire culture is scifi now? Why every blockbuster movie is scifi superheroes? Why every video game has dragons or starships or zombies? Why protesters hold Andor signs? Or why every vision of scifi from androids to AI is coming true?

It’s because science fiction, from Frankenstein onward, has continued this myth-making function. Science fiction is the 21st century mythos. Giving new answers to the eternal questions of humankind.

What is this reality? What is beyond those skies?

Who or what made all of this and why?

What came before life and what comes after death?

What am I? What is human?

It was to find answers to these questions that I began my video series Science Fiction : writing the 21st century mythos, the series which became this channel

Become a channel member on here, YouTube or Patreon and you will find all my videos and workshops, my course The Rhetoric of Story, ten years of learning in just 5 hours of video, and my audio commentaries.

Thank you.