Ladies and gentlemen, allow me to direct your attention to the shortlist for the Kitschies, the annual awards organised by the folks at the Pornokitsch blog, which is quickly establishing itself as one of the two or three most relevant awards in fantastic literature. And the nominated novels are:

- The Enterprise of Death by Jesse Bullington (Orbit)

- Embassytown by China Miéville (Tor)

- A Monster Calls by Patrick Ness and Siobhan Dowd (Walker Books)

- The Testament of Jessie Lamb by Jane Rogers (Sandstone)

- Osama: A Novel by Lavie Tidhar (PS Publishing)

There are two additional categories for best debut and best cover, information here, both strong shortlists but I want to focus attention here on the best novel category. Because not only is this a strong shortlist, but an important one for fantastic literature, because it really asks the question of how seriously we take ourselves, or expect to be taken by others.

This has not been a good year for SF awards. The Hugo and Nebulas both came under criticism for shortlists primarily determined by partisan fan factions rather than quality writing, and the British Fantasy Society awards literally collapsed under the weight of their own nepotism. Earlier comments on this issue lead me in to a protracted argument with John Scalzi through the medium of Twitter. John didn’t seem to think having awards shortlists full of bad books was a problem because, you know, quality is just a subjective issue and people have different tastes and any suggestion that more than a few of these books were were incredibly lightweight was ‘kvetching’.

So the Kitschies shortlist leaps out as actually doing that thing that awards should do, which is awarding the best work in their field. And in those terms I doubt there will be a stronger shortlist in any award for fantastic literature this year.

Jesse Bullington’s work came to prominence after an unusual call for attention through Jeff Vandermeer, and his two novels to date have established him as one of the most talented prose writers out there, shaping incredibly dark worlds of deep moral uncertainty. The Testament of Jessie Lamb became one of the few works of science fiction ever to pick up a Booker prize longlist nomination in 2011. Embassytown is a novel I’ve already heaped praise upon in The Guardian for its treatment of radical political themes through the lens of SF metaphor. Osama : A Novel has placed Lavie Tidhar in the top rank of todays SF writers for its intelligent and complex examination of post-911 politics, filtered through a Philip K Dick influenced alternative reality. But much as I like these books, A Monster Calls by Patrick Ness and Siobhan Dowd is quite simply a masterpiece, continuing Ness’s powerful exploration of themes of violence and male identity, and probably deserves to win any award shortlist it finds itself on this year.

In different ways all of the books on this shortlist demonstrate what it is that is truly great in fantastic literature. They are all great books by any definition. Books with heart and soul, and also with meaning. Books we can find insight in, and learn about what it is to be human, even in a world as weird and strange as our own, and which use the metaphors of fantastic literature to create that insight. They are intelligent works of fantastic literature, that deserve to be recognised and rewarded as such.

Fantastic literature is a broad church. Many of the congregation are there for a bit zombie apocalypse or steampunk adventure. And that’s OK. Really it is. A world where every novel had the intellectual heft of Mieville would be a hard one to enjoy. Absolutely true. But when it comes to awards, are we really doing ourselves justice by lauding popcorn novels with major prizes? I’m going to fully enjoy John Carter of Mars when it hits our screens, but I would be profoundly disappointed if it took the Oscar for best movie or the Palm d’Or. And I would start to take those awards less seriously, then ignore them all together, if films without any substance won them often. Awards stand or fall on the basis of the quality they reward. Some of SFs major awards may be falling by that measure. But it seems new awards are there to replace them.

Related articles

- What the Booker prize really excludes (guardian.co.uk)

- Tor.com 2011 Readers’ Choice Awards Update 01/12 (tor.com)

- Why Science Fiction is the literature of change (damiengwalter.com)

- A Monster Calls by Patrick Ness: review (telegraph.co.uk)

I think there is certainly a measure of subjective opinion, but to relativize to the point where all novels are somehow interchangeable in awards nominations is a bit much. I have only read two of the novels on this list, but all of them have gotten not just good reviews, but thoughtful responses. I’m writing about OSAMA right now and I’ll go back to EMBASSYTOWN soon. I really want to read TESTAMENT but I have not found a reasonably priced copy yet.

It’s a good list. Hopefully it will stimulate some worthwhile discussion.

LikeLike

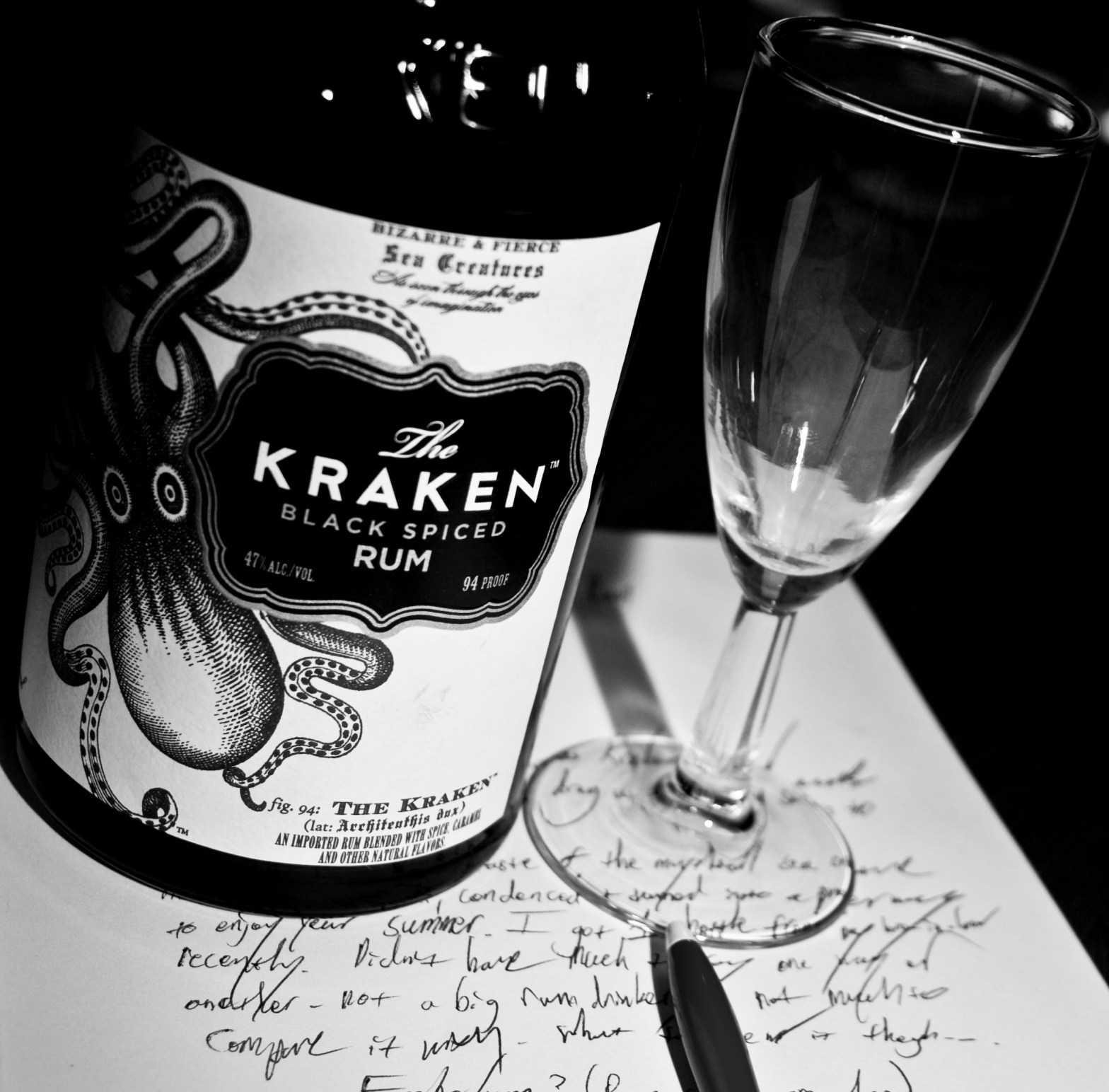

Reward Intelligent fantastic literature… with Kraken Rum!

LikeLike

I just went looking for Kraken rum. Could find none however hard I looked.

LikeLike

The Case bar and shop on Friar Lane. That’s where I bought my bottle a couple of months back.

LikeLike

I saw it in my local branch of Peckhams. Piity I am not a fan of rum.

LikeLike

Everyone has seen the rum except me!

LikeLike

It is not ordinary rum. It has a most exotic and startling taste. I am in a position to reveal the true text of a classic song, till now only available in a bowdlerised version:

“Fifteen men raid a Kraken chest,

Yo-ho-ho and a bottle of rum;

Drinking the Kraken has done for the rest,

Yo-ho-ho and a bottle of rum.”

It should be sipped, rather than chug-a-lugged in pirate fashion.

LikeLike

I’m lead to believe it is 94% proof�how it manages to taste so nice at that kind of potency I do not know.

LikeLike

94 degrees proof is roughly about 35% by volume, IIRC. Equivalent to a cheap brandy or gin, quite strong for a liqueur. Most quality spirits are 40% by volume, but are naturally diluted by the addition of flavourings to make a liqueur.

Historically, spirits were proofed to the Exciseman by placing gunpowder on top of a barrel, pouring some of the liquor on it, and trying to ignite. If the powder burned, the spirit was ‘proof’. If not, it was too wet and not a proof spirit. In the modern era, proof turned out to be about 37.5 % by volume, and was divided into 100 degrees. The system was metricated away by the Fred Teeth government (IIRC), and bottles have since been labelled as % alcohol by volume.

LikeLike

OK so I’ve googled it and one site says it’s 40% and another says it’s 94 proof…could I possibly have misremembered the conversion factor after all these years? Surely not…must be somebody else’s fault.

LikeLike

Here’s an episode of a Canadian show from the early 90s, PRISONERS OF GRAVITY, all about awards. I recommend watching episodes of this, despite some random silliness–especially in the beginning. There are interviews with some fantastic SF/F writers, etc: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-M0uT6WhJsQ

LikeLike

Many Sainsbury’s have it as well (including the one in Nine Elms)

LikeLike

Where is Nine Elms?

Can I land my copter there?

LikeLike

Reblogged this on S.A. Barton: Seriously Eclectic.

LikeLike