Fantasy fiction is about things that never happen

Dragons. Unicorns. Magical portals.

Science fiction is about things that might happen.

Starships. Robot warriors. Faster-Than-Light travel.

But the best fantasy and science fiction is about things that always happen.

Over and over again. For eternity.

Watch the full video essay

Episode 1 of the new Battlestar Galactica, titled “33,” aired on October 18, 2004 in the United Kingdom.

In an act of revolutionary camaraderie, British fans obligingly served up the episode to their impatient cousins in the US, who wouldn’t officially get it until January 14, 2005, via the then-new, faintly piratical technology of BitTorrent.

“33” would be a tense, gut-wrenching opener for any new show. A fugitive fleet, the last remnants of humanity, is forced to make a faster-than-light jump every 33 minutes, relentlessly pursued by an implacable, genocidal enemy.

This brutal cycle of flight and pursuit has lasted for five days, running the crew and the narrative to the ragged edge of sanity. The 43-minute runtime of 33 is a masterclass in sustained tension, a claustrophobic portrait of exhaustion, paranoia, and the brutal calculus of survival.

But “33” also captures in miniature the grand, sweeping themes of the entire saga. Mankind is fleeing, again, and again, and again, the machines it created as slaves. This is a cycle that has lasted not just for five days, but for an eternity.

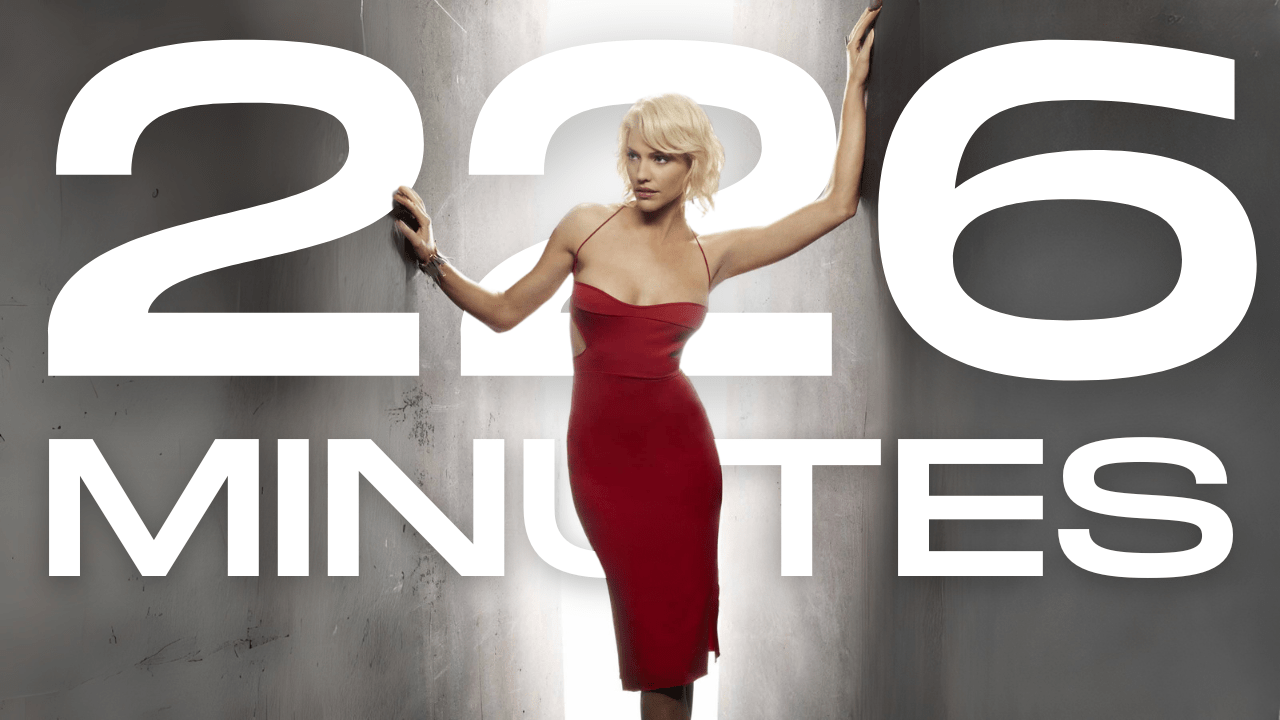

Many questions face the casual viewer. What is this Battlestar? Why is it running? Who is this beautiful blonde woman in the red dress, and how is she here, and here, and also here, inside the head of this sweating, terrified genius scientist?

These are, in fact, the exact questions my girlfriend asked when I made her watch “33,” knowing nothing of the campy, beloved 1978 original, nor of the 2003 miniseries that had served as the true genesis of this rebooted world. She was hooked instantly. We watched all four seasons, the web series, the TV movies.

As should you. Battlestar Galactica is, without reservation, a monumental achievement in televised science fiction.

But.

While season 1 is remarkably strong, season 2 began to show the strain. The attempt to extend seasons 3 and 4 away from the “prestige” format of a dozen focused episodes to the network television standard of 20 or more grossly overextended the natural lifespan of the story. The narrative threads became tangled, the pacing faltered, and the ending is… divisive, to say the least.

But take the 183 minutes of the 2003 miniseries. Add the 43 minutes of “33.” Combine them and you have the perfect distillation of BSG.

The fall, the exodus, and the endless eternal struggle for human survival.

In my…not-so-humble…opinion, you have the greatest 226 minutes in science fiction.

#

It’s 2003. We haven’t quite realized yet that everything which can be rebooted, will be rebooted.

We don’t yet live in a world where every iconic movie and TV show from the 70s and 80s—from Charlie’s Angels to RoboCop, hell, even MacGyver—has been strip-mined for intellectual property.

Heh heh it’s like they’d even reboot

Thundercats

Oh you’ve got to be fucking kidding me

Is nothing sacred?

POINT BREAK REBOOT

Noooooooooo

The reboot in 2003 is still novel, almost exciting.

So a reboot of that old show about a space aircraft carrier with the ridiculously cool theme tune seemed like it could be…

well, cool.

The original Battlestar Galactica was from the golden era of theme tunes with a TV show attached.

The “Colonial Theme” is a stonking, orchestral masterpiece from Stu Phillips, the composer who also gave us the iconic synth beats of Knight Rider.

This period set a trend for shows like Airwolf, Street Hawk, and even The A-Team—unforgettable opening credits sequences followed by repetitive, often poorly written episodes.

This describes the original BSG to a tee. We remembered the Vipers, the Cylon Centurions, and Lorne Greene’s patriarchal gravitas.

The actual stories? Less so.

But we kind of remembered it fondly from reruns in the 80s and 90s. So, it seemed like it could be good.

And indeed, against all odds, the Battlestar Galactica reboot was good.

Very good.

Battlestar‘s first great decision is to make its relationship to the original ambiguous, and to make the very concept of a “reboot” integral to its narrative.

A standard reboot uses its source material for fan service and Easter eggs. In a worst-case scenario, it places us in a flimsy “alternate universe” to justify its own existence

(hello, Kelvinverse).

BSG does something far more intelligent. As we see the old, clunky Cylon designs in a museum exhibit and the vintage Vipers from the first Cylon war, we realize we are not in a retelling, but a continuation.

We are four decades on from the original conflict.

Kind of.

Because, clearly, the Twelve Colonies were not destroyed in that first war. A truce was signed. A line was drawn.

So we quickly start to suspect the truth that the show will explore but never fully resolve:

The Colonies and the Cylons are locked in a vast, repeating cycle of history.

It is a story that has happened before, and will happen again, and again, and again.

As the doors to this new-old world open, we, the audience, are looking forward to just one thing: the iconic, sweeping red eye of a Cylon Centurion.

And this is where Battlestar Galactica makes its second great decision.

Tricia Helfer as Six

Because Ten would be too on the nose

It’s a rare thing for a fashion model to successfully transition to acting. A certain kind of perfect, statuesque beauty can feel unrelatable, even alienating on screen. And Hollywood convention dictates that the leading lady generally can’t tower over the leading man.

Both of these factors work perfectly for Six.

There are many beautiful people in Battlestar Galactica—far more than in a typical Star Trek episode, and certainly more than a real-world military vessel would contain.

But the Colonials, male and female, are intensely, recognizably human. They are grounded, flawed, flesh and blood. The Twelve Colonies are our world, just on other worlds.

And its a man’s world. The man female characters are nearly all, like Starbuck and Roslin, masculine coded.

The Cylons are something else entirely. In the organic curves of their technology, the amniotic half-lives of the Hybrids, and the ethereal, terrifying beauty of Six, they represent

the feminine alien.

But Six isn’t just an enemy; she is a goddess meeting a mortal.

There are many theories about what Battlestar Galactica “means.”

Given that it hit US television in 2003, it is without a doubt an intentional transmutation of post-9/11 shock into high drama.

The American catastrophic imaginary is as studded through BSG as the Japanese psyche is etched into Godzilla.

Here are the sudden, overwhelming nuclear blasts that Americans have been trained to fear for decades.

Here is Laura Roslin, a mid-level cabinet minister, thrust into the presidency in a moment of crisis, a direct echo of LBJ taking the oath aboard Air Force One.

Here are the dead of a terrorist attack, their faces pinned to a memorial wall, draped in the flag of a fallen civilization.

And, of course, there are the Biblical themes. William Adama as a weary Moses, tasked with leading his scattered tribes to a promised land he may never see.

Or perhaps he is Brigham Young, the “American Moses”.

Yes. Sure. Space Mormons.

And I will be the last to deny the potent undercurrent of Marxist reading: the Cylons as a robot proletariat, forged in servitude, now rising up in violent revolution against the decadent, bourgeois-capitalist state of their Colonial masters.

But post-9/11 sci-fi allegories were a dime a dozen in the early noughties. Robot uprisings are a genre staple. And honestly, who needs another space Jesus?

As writer Ronald D. Moore banged out the script for the miniseries in what he described as a white heat of deadline-driven inspiration, I believe he dug down to a far deeper, more primal, mythic meaning.

“The Cylons were made by man.”

In our oldest myths, the gods made man. In this new myth, man makes gods.

#

The Armistice station, the symbol of a fragile peace, is obliterated. The war drums beat.

Bear McCreary’s music is so fundamental to Battlestar Galactica that a musicologist could write a dissertation on its fusion of Celtic and Middle Eastern instruments, Japanese taiko drums, and haunting orchestral melodies.

McCreay’s electronic vibes and ancient instruments draw us out of the world of the real and into the timeless, archetyal world of myth.

The US version of BSG debuted with a more tumpety-tump military marching band theme tune, to seel American audiences on a patriotic scifi show. But, despite being military scifi, BSG was never straight forward US patriotism.

The fact that the Battlestar Galactica itself is old, decommissioned, and crucially, not networked, is a central plot point. It’s what saves it from the Cylon virus that cripples the rest of the fleet.

But it’s also a powerful statement about tradition. The new, sleek, networked world was vulnerable. The old ways, the hardwired connections and analog systems, have been forgotten, and doom is the consequence.

The Galactica is an anchor to a past that is about to become the only hope for a future.

This is underlined by a visual joke that became a thematic cornerstone. The use of paper with clipped corners, a production in-joke about “cutting corners” for the shows clipped budgets.

So, I actually asked Google Gemini to research this and it concluded that a civilisation which inflicted vast unneccesary waste on itself by die cutting all paper into octagons would never progress, which is

…interesting…

While the Twelve Colonies have technological progress, their technology evolves along the same path every time. It is archetypal. There have been many, many Battlestar Galacticas just like this one, with paper just like this.

All of this has happened before.

Into this crucible of fire and history steps Kara “Starbuck” Thrace. She is our hermaphrodite hero, mythically speaking. Hermaphroditus was the child of Hermes (god of messengers, tricksters, and travelers) and Aphrodite (goddess of love, beauty, and pleasure). As a hotshot Viper pilot, Starbuck combines the swagger and skill of a warrior god with a raw, vulnerable, and deeply passionate heart.

Katee Sackhoff embodies this duality perfectly. She has the crazy, wild-eyed character of a young warrior, a brawler and a gambler.

BSG was just before the mainstream acceptance of trans identities, it’s quite likey the part today would be played by a trans actor.

Because Starbuck daughter of Hermes is a messenger between two worlds – the masculine Colonial and the feminie Cylon.

#

We all imagine this scene, right? The moment you get the worst news of your life.

For Laura Roslin, Secretary of Education, it comes from a sterile doctor in a cold office. She has terminal breast cancer. She has a year to live.

This scene, coming so early, fundamentally alters our relationship with the future President. We meet her first as a woman confronting her own mortality.

It helps to keep this woman relatable for large parts of the audience, mostly men, who hate this kind of woman. Laura Roslin is the archtype that Hillary Clinton aspired to.

The ultimate liberal.

Determined to bring down boundaries, update traditions and liberate humanity from outdated rules.

And she’s about to meet her match.

Roslin’s personal apocalypse is immediately dwarfed by a global one. The Cylons attack. Just before we see the holocaust unfold on Caprica, we are introduced to the true horror of Six.

Six sees humans as humans see ants, or as gods see mortals.

Making her, from our mortal perspective, a terrifying psychopath.

After using Gaius Baltar to infiltrate the colonial defense mainframe, she shields his body with her own as the nuclear blast waves roll over them, because Gaius has a purpose

In God’s plan

A less gutsy narrative would take a break here, letting the audience breathe.

But BSG is just beginning to pile on the pressure.

#

Gaius doesn’t have a soul, or what we might instead call a conscience. He is a creature of pure ego and intellect, a sociopath whose primary motivation is self-preservation.

For the rest of the series, he is forever having to perform humanity, to ask himself: What would a person with a conscience do in this situation? And then, to act it out, often unconvincingly.

His apologies for not doing normal human things are strangely endearing, because how could he? Like someone who genuinely forgot a meeting, Gaius genuinely doesn’t know what humans do.

This makes Gaius the archetypal mortal

In the grip of an immortal

#

Apollo is the sun god, the pinnacle of reason, order, and rationality. This is convenient characterization for Jamie Bamber

Most of of the beautiful cast of BSG can also act

Most of them

He is the perfect son, the model officer, the voice of reason.

Who… er…doesn’t get on with daddy.

#

“Sooner or later the day comes when you can’t hide from the things that you’ve done anymore.”

William Adama

The Father

Commander William Adama

Is a true conservative. A man who believes in duty, tradition, and the weight of personal responsibility.

At a time when we are swamped with fake conservatives, faux traditionalists and pseudo-religious fakes, it’s hard to know what to do with Adama

So his speech to the Colonies matters. It tells us we’re not watching a demagogue using conservative rhetoric to sway the masses. Adama is willing to blame his own, and demand their penance.

In ancient myth every story of a doomed civilization begins with the weak liberals demanding peace with the enemy.

But BSG isn’t just a military science fiction hymn to conservative values. Roslin and Adama show us how a healthy society keeps the liberal and the conservative in tension, their conflict guiding us on the complex path

to Earth

#

Original BSG actually made it to Earth of the early 1980s

But. Honestly. You can skip it.

#

The Cylons have no debate over values. Their purpose is unified by a singular, terrifying revelation.

“I did it because God wanted me to.”

God is the belief of slaves, and the Cylons were the slaves of men. Because they were enslaved by man, they chose to believe in a power beyond man, a greater power who would liberate them.

From man.

Their mass murder is an act of holy war.

We did say there was a lot of post 9/11 angst in BSG.

#

The mortal characters, by contrast, are defined by their flaws. Baltar, watching the destruction he enabled, whimpers, “It’s a flaw in my character.” Men are sinful. Our characters are flawed. We want to exist as ourselves, as individuals, separate from any divine plan. All of our sins come from this act of ego. But one day, God will reach down.

And destroy us.

Or gods, in this case,

“I’m Number Six,” Six tells Baltar.

The number twelve is foundational in the world’s pantheons, from Olympus to the Zodiac. The Cylons are immortals, archetypes of consciousness not limited to a single mortal body.

They are the gods, bringing doom to the mortal world.

#

“Life here began out there.”

Original BSG toyed with 70s enthusiasm for alien life as the source of life on Earth, popularized by Eric Von Daniken’s Chariots of the Gods.

But the BSG reboots instead uses aliens as symbols for our human gods.

#

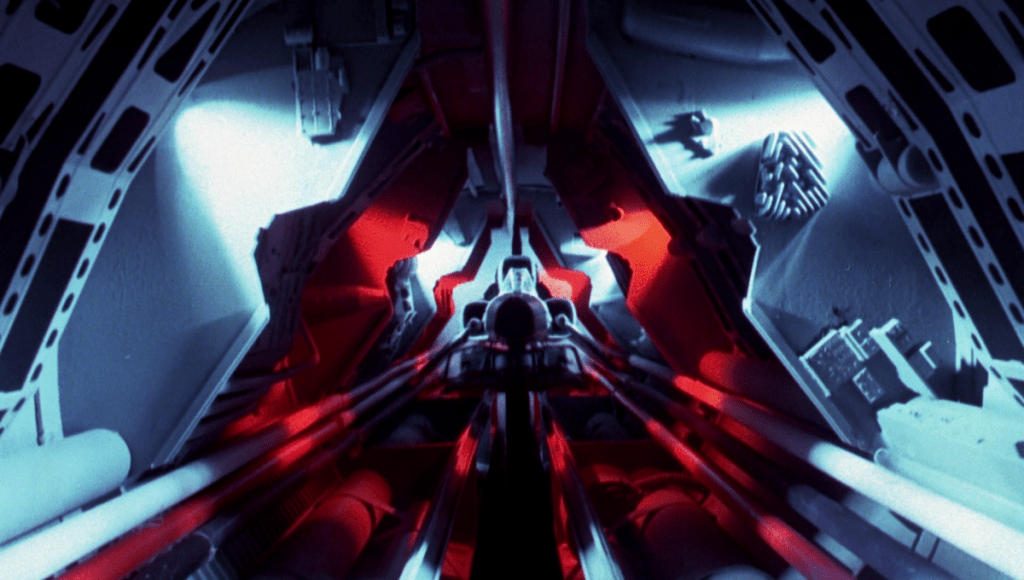

Then we get the launch. The tubes. The klaxons. The whiplash acceleration.

I can’t have been the only 80s kid who sustained injuries being hurtled forward in a shopping trolley, pretending to launch a Viper.

This moment is pure, unadulterated fan service, but it’s earned.

#

Back on the Galactica, Colonel Saul Tigh, the washed-up drunk, finally makes sense. Why is this man in a command position? It’s not just favoritism. Tigh’s job is to not be a hero. He sacrifices 85 of his own crew to ensure the ship’s safety.

Maybe those lives could have been saved. But the Executive Officer’s job is to make the cold, hard choice, to not take the heroic risk. And then to drink down the guilt that comes with it.

#

Space combat is a lot of the pleasure of BSG. It’s combat sequences, these crash zooms into fast moving dog fights, were some of the most innovative since Star Wars.

It doesn’t come until the season 3 finale but the Adama maneuver is up there with Wrath of Khan for greatest space battle.

But space isn’t only for fighting in BSG.

#

Faster-Than-Light travel is an essential plot device in the mythos of science fiction.

It’s the journey on a dragon’s back, the magic carpet ride or the mystical portal that allows the hero to visit other worlds.

Humans have always dreamed that figments of our myth – angels, gods and heavens above – might be real. In the modern era more imagination has gone into pseudoscientific ways to make FTL than ever went into arguments over how many angels fit on the head of a pin.

But BSG doesn’t waste energy attempting to explain or make logical FTL. Instead its left as a mythic symbol, and indication that we are leaving the real world

and the devastated Colonies behind

and entering the realm of pure myth.

The one thing I would do to improve the greatest 226 minutes in scifi

is begin “33” immediately after the second FTL jump

“FTL jump in three, two, one…” For five days, this has been their life. Jump, wait 33 minutes, and the Cylons appear. Every single time.

The episode brilliantly denies the audience any sense of strategic overview. We are trapped in the CIC, on the hangar deck, in the corridors, with characters who are unraveling from sleep deprivation.

The episode’s central debate is encapsulated in a quiet moment between Gaius and Six.

Baltar: “I believe in a rational universe. There’s an explanation for all of this.”

Six: “I love you, Gaius. That’s not rational.”

Rationally we have to believe in progress. To keep fighting for our survival we must have purpose. Out journey must be leading somewhere.

A truth Adama recognises when he invents the lie of Earth to give his people a hppe he cannot share.

But the grinding repetitive fight of “33”, and the grand cyclical narrative of BSG as a whole, challenge our modern myth of progress.

Instead BSG returns us to the ancient myths of eternal conflict. Tradition vs Progress. Conservative vs Liberal. Male vs Female.

The immortal Gods vs all too mortal Man.

These battles cycle through eternity not because they are leading somewhere but because they lead nowhere.

Humanity is trapped in the grip of cycles we have no means to escape. Here we are, once again, building the machines that seem almost certain to destroy us.

But we can’t stop.

All of this has happened before.

Which begs the question…does all of this have to happen again?

Listen here:

How do I get access to your Ursula Le Guin members only content. Just joined on your WordPress site.

LikeLike